Corresponding Author for Proof

Christopher Surek

7901 W. 135th Street

Overland Park, KS 66223

Email: csurek@gmail.com

Twitter/Instagram: @dr.chrissurek

Coauthor Address

Jacob Grow

3600 Park E Dr, Apt 145

Beachwood, OH 44122

P (M): 812-344-0766

Email: jngrow812@gmail.com

Twitter/Instagram: @DrJacobGrow

Disclosures: Dr. Surek is a consultant for Allergan, Galderma and Cypris Medical

SYNOPSIS

With aging, there is a loss of bony foundational support progression of soft tissue laxity and descent of the midface. Aside from formal surgical intervention, restoration of volume and youthful contour in this area can be reliably and safely achieved using hyaluronic acid-based filler products. By targeting the well-defined pre–zygomatic space with precise technique, results are consistent, and complications are minimized. In this chapter, we describe our reproducible, anatomical approach to midface rejuvenation.

Introduction

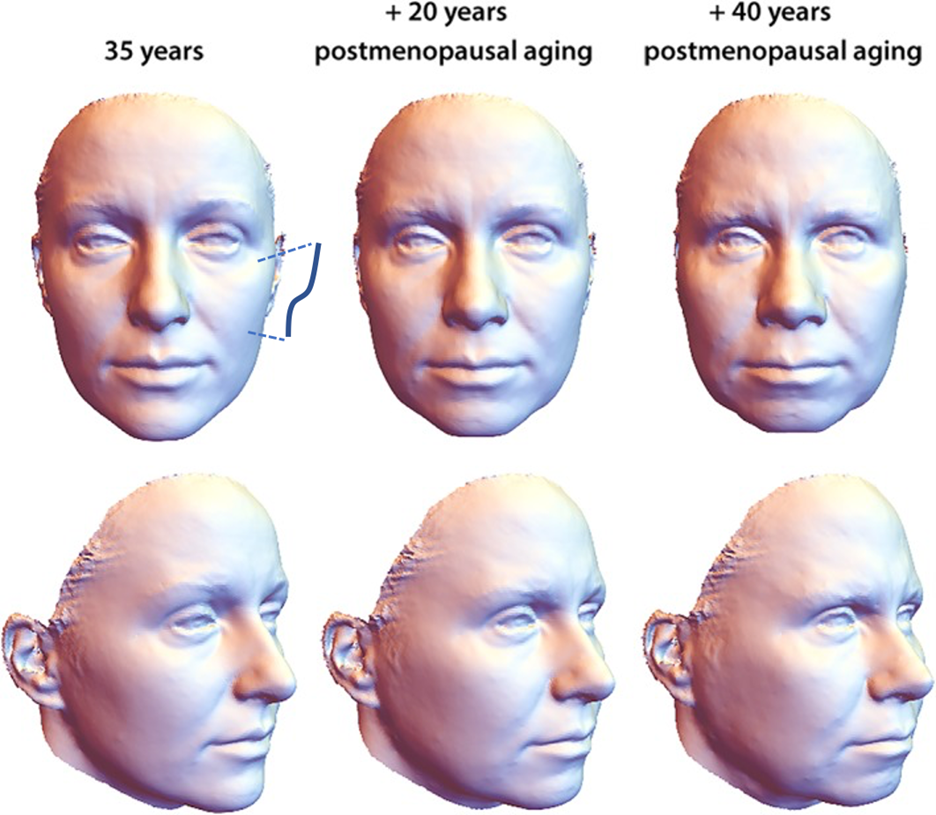

When making an aesthetic impact on the face, it is paramount to establish clear treatment goals that coincide with the desires of the patient. As we focus on the midface, we must first define the aesthetic ideal we are striving to create, knowing that there are predictable changes that occur with aging in this region. A youthful, “plump” cheek possesses greatest fullness laterally over the zygoma, creating what is referred to as the ogee curve of an attractive, oval facial shape. With age, loss of bony foundational support, soft tissue laxity and descent result in the appearance of a deflated midface and progressive transition to a more square facial shape (Figure 1).1 These changes are accelerated and accentuated by extrinsic factors, primarily sun damage andsmoking.2,3,4 As we identify these changes, our overarching goal for rejuvenation of the midface will therefore be not only to provide volume, but to do so in a specific way that restores this attractive shape.

Mechanisms for Rejuvenation

For any procedure to be worthwhile, results must be predictable and long-lasting relative to the patient factors of pain, cost, longevity and recovery. We therefore cannot dismiss that often the most definitive option for treating the aging midface is through a surgical facelift. However, as we weigh the aforementioned patient factors with goals of treatment, mental preparedness, and stage of life, there are certainly non-surgical techniques that can meet our aesthetic goals and provide a significant improvement in midface shape and volume. The most common modality for non-surgical rejuvenation of the midface is through injectables, namely hyaluronic acid and less commonly poly-L-lactic acid and calcium hydroxyapatite. Provided in an office setting, results with HA volumization are instant with virtually no downtime and relatively low risk if performed by a well-educated injector. The desire for these procedures has increased dramatically over the years, with nearly 750,000 facial injectables performed in 2019 which represents a relative increase of 25% over the last 5 years.6 The average age of patients seeking these interventions has also decreased over this time frame, suggesting a desire not only for restoration in older patients but also augmentation in younger patients.

Although our focus will be specifically on the use of hyaluronic acid fillers in the midface, these techniques may also be applied to the use of autologous fat grafting and more recently, utilization of acellular adipose allograft that may provide longer lasting results.7 We also acknowledge the use of internal suturing techniques commonly known as “thread lifts” that simulate the effects of surgical facelift in the malar area. However, this is a far less proven modality for restoration of the midface and beyond the scope of this chapter.

Relevant Anatomy

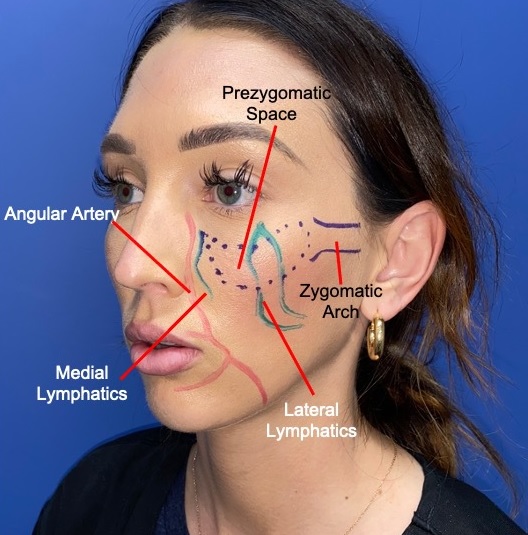

In order to ensure safe, predictable and reproducible results with injection, one must first understand the basic anatomy of the treatment region. The midface can be simplified into a superficial and deep plane, which consist of well-defined fat pads and potential spaces at each level.8 The superficial and deep planes are divided by the Superficial Musculoaponeuortic System (SMAS). The SMAS can act as a depth gauge for injectors as they attempt maneuver between planes.9 For the purposes of injection anatomy specific to this region, the prezygomatic space is a safe target for volumization within the deeper plane. Its borders are consistent, lying deep to the orbicularis oculi muscle and suborbicularis oculi fat, bounded superiorly by the orbital retaining ligament and inferiorly by the zygomaticocutaneous ligament arcade (Figure 2). Preperioesteal fat composes the floor of this space, providing a natural, anatomic glide plane. Laterally, the space is bordered by the lateral orbital thickening, just medial to the zygomatic arch.

Prezygomatic space (blue) superimposed on a youthful female face. The major arterial vasculature is also outlined in red. Care should be taken in this region to avoid accidental intravascular injection. Emphasis should be placed on lateral volumization once the PZS has been entered with the blunt injection canula.

Given the potentially devastating complications of soft tissue necrosis and even blindness following inadvertent intra-arterial injection, appreciating the vascular anatomy of this region is important. The primary arterial blood supply of the midface comes from the continuation of the facial artery, a branch of the external carotid artery system. As the facial artery traverses over the body of the mandible, it continues as the angular artery above the level of the oral commissure, approximately 3.5 centimeters from midline at the level of the supratip break.10 This vessel continues onto the nasal sidewall, ultimately conjoining with the dorsal nasal branch of the ophthalmic artery after giving off the lateral nasal artery. It should be noted that this arterial system lies within or below the SMAS until it reaches the alar facial groove, where it becomes more superficial and therefore more susceptible to incidental injection and injury. Variations also exist where the course of the vessel may be more lateral, and consequently overlap with our target zone for midcheek volumization. This makes the plane of injection and specific technique all the more important. Finally, the primary sensory contribution to the region comes from the infraorbital neurovascular bundle, located deep along the midpupillary line at the junction of the lid-cheek crease and nasojugal crease.11 This becomes useful, as it is not uncommon and at times desirable to produce anesthesia in this sensory distribution while injecting with lidocaine-laced filler products, especially when preceding HA filler augmentation to the lips.

Lastly, the lymphatic anatomy of the midface and lower eyelid are pertinent to injection procedures. The lateral chain of lymphatics are comprised of a superficial and deep channel. The superficial channel runs above the orbicularis muscle within the superficial fat whereas the deep chain runs below the orbicularis muscle and through the floor of the pre-zygomatic space. It has been postulated that disruption of the lateral superficial lymphatic system may result in an iatrogenic malar mound. The resulting edema becomes contained between the cutaneous insertions of the orbital retaining ligament and zygomaticocutaneous ligaments.10

Methods: Product Choice

In determining the best technique for recreating an attractive shape in the midface, we must first understand the basics of HA filler characteristics so that the most appropriate product is utilized. On a molecular level, the degree of cross-linking between individual HA molecules determines its G’ value. More specifically, the higher the G’, the more resistant a product will be to extrinsic deformational forces when a stress is applied. Put even more simply, G’ can be considered the hardness of a specific filler. Additionally, variability in hydrodynamics between HA filler products exist, as some formulations will absorb more water than others, creating the perception of a lifting effect as the filler expands following initial injection. As a general rule of thumb, more viscous, lower G’ fillers are used superficially to treat fine lines and wrinkles, while higher G’ products provide volume in deeper planes and are more resistant to the sheering forces of facial animation.

Focusing on the midface, we want to restore the loss of bony and soft tissue support to recreate youthful shape. Therefore, utilization of a high G’ HA filler with high absorptive capacity can provide us with a predictable result. This could typically include either Juvéderm Voluma® or Resylane® Lyft, both of which have FDA approval for cosmetic treatment in this area (AbbVie, Inc., Chicago, IL). However, there are several products available that can be effective in this region for injection.

Methods: Injection Technique

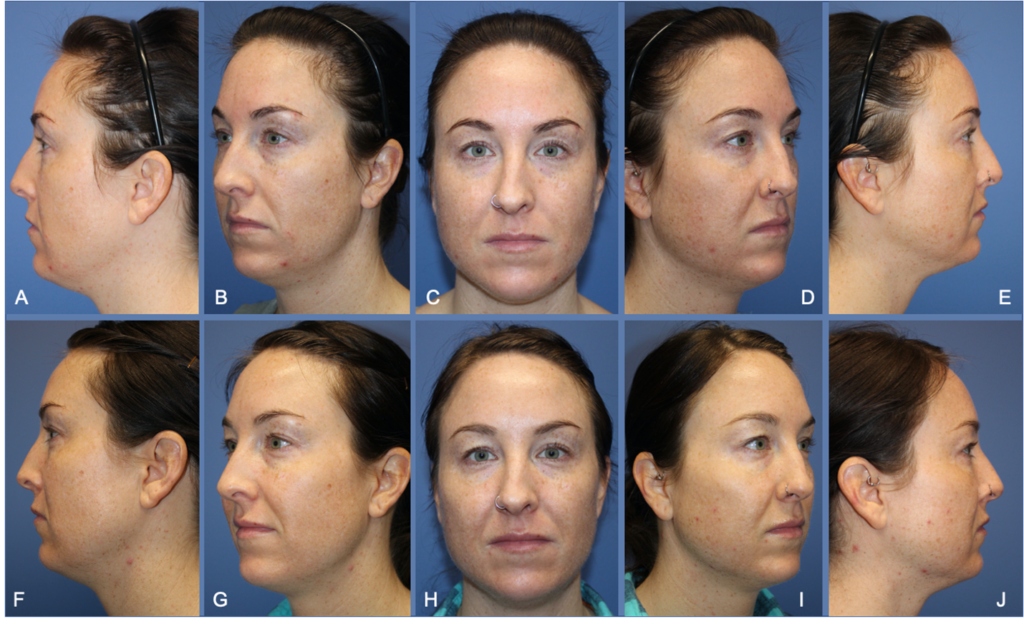

Especially for the novice injector, taking the extra time to mark the target area portends success. As previously described, our primary target zone for volumization will be the prezygomatic space. A reliable method we have found to access this space is to approach it laterally with a blunt 25-gauge, 1.5 inch cannula. More specifically, a port site is made approximately 1.5cm inferolateral to the lateral canthus. The injector then uses a “pinch and pull” technique to lift outward on the lateral portion of the prezygomatic space. In a deep plane, the cannula enters into the space following a palpable and audible penetration of the prezygomatic space capsule, commonly heralded by a “pop.” The cannula will then pass freely throughout the space, allowing for gradual volumization with an emphasis on lateral filling. Typical volume may range between 0.5ml to 1.5ml per side and should be done slowly and sequentially. Gentle massage may also assist in distributing the product into the desired location. Given the lateral limitation of the PZS, volumization at the zygoma onto the zygomatic arch will also help to augment shape and prevent a sharp transition laterally. At times following initial injection, the treated region may have a stuck-on appearance especially prior to secondary hydrophilic expansion, so blending laterally onto the zygomatic arch is useful. This can be done safely with a 30 or 32-gauge needle in small, sequentially aliquots of the same filler product bolused down onto bone.

Following injection, patients are advised to avoid strenuous physical activity for 24 hours. Unless perioral filler is also given or the patient has a history of cold sores, antiviral prophylaxis for herpes outbreak is not routinely prescribed. Patients should also be educated on the secondary hydrophilic volume expansion that will occur over the following 2-3 days after initial injection, which helps to further blend and lift the treated area and surrounding soft tissue. Cold compress can be used if desired, although pain and ecchymosis is rare. We also do not routinely instruct patients to massage the treatment area. On average, results will last at least 9 months, and not uncommonly, well over a year.

Common Errors/Complications

Perhaps the most common mistake encountered when injecting the midface is disproportionate volume placement. Examples of this error are commonly encountered across social media by a full anterior midface in the maxillary region which appears grossly unnatural and overdone. As a result, many prospective patients shy away from “cheek fillers” for this reason, making it imperative to educate your patients appropriately on your goals of treatment and desired shape. In the event that product is placed either in the wrong location or an area is overtreated, correction can be accomplished with progressive infiltration of hyaluronidase, which dissolves the filler almost instantaneously.

Malar edema can be seen immediately after the injection due to anatomic disruption of the lymphatics or suboptimal selection of filler product. Malar edema can also occur in a delayed fashion several months following injection as the filler product undergoes degradation and/or resorption. Treatment algorithms should include anti-inflammatory, anti-biofilm and anti-histamine regimens as well as lymphatic massage and compresses.

Infection following injection is exceedingly rare and can be treated with oral antibiotics that preferably cover MRSA, doxycycline being our primary choice. In the event of a herpetic outbreak, prompt treatment with valacyclovir is initiated and the patient is monitored closely so as to prevent further complication such as ocular involvement.

Although management of arterial injection of HA filler is well beyond the scope of this chapter, the need for prompt treatment with hyaluronidase cannot be overstated. We will not perform these injections on any patient without hyaluronidase available.

References

- Lambros V, Amos G. Three-Dimensional Facial Averaging: A Tool for Understanding Facial Aging. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016 Dec;138(6):980e-982e.

- Okada HC, Alleyne B, Varghai K, et al. Facial changes caused by smoking: a comparison between smoking and nonsmoking identical twins. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013 Nov;132(5):1085-92

- Sams WM. Sun-induced aging. Clinical and laboratory observations in man. Dermatol Clin. 1986 Jul;4(3):509-16.

- Flament F, Bazin R, Laquieze S, et al. Effect of the sun on visible clinical signs of aging in Caucasian skin. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2013 Sep 27;6:221-32.

- Windhager S, Mitteroecker P, Rupić I, Lauc T, Polašek O, Schaefer K. Facial aging trajectories: A common shape pattern in male and female faces is disrupted after menopause. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2019 Aug; 169(4): 678–688. Published online 2019 Jun 12. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.23878

- Cosmetic surgery national data bank statistics. Aesthet Surg J. 2020;40(Suppl 1):1-26

- Kokai LE, Sivak WN, Schilling BK, et al. Clinical Evaluation of an Off-the-Shelf Allogeneic Adipose Matrix for Soft Tissue Reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2020 Jan 27;8(1):e2574.

- Rohrich RJ, Pessa JE. The fat compartments of the face: anatomy and clinical implications for cosmetic surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007 Jun;119(7):2219-27.

- Surek CC. Facial Anatomy for Filler Injection: The Superficial Musculoaponeurotic System (SMAS) Is Not Just for Facelifting. Clin Plast Surg. 2019 Oct;46(4):603-612.

- Lamb JP, Surek CC. Facial Volumization An Anatomic Approach. New York: Thieme; 2018.

- Pessa J, Rohrich R. Facial Topography: Clinical Anatomy of the Face. St. Louis, MO: Quality Medical Publishing; 2012