Abstract/Synopsis:

This chapter reviews the fundamentals of aesthetic rejuvenation of the perioral area and lip augmentation using non-invasive techniques. Also covered are an in-depth look at ideal lip proportions, the anatomy of the lips and the anatomic changes that occur in the lips and perioral area over time, as well as important considerations for consultation with the patient. We review injection techniques for using fillers in this area, including both needle and cannula methods, and provide video demonstrations of both methods. A review of neuromodulators and how they can assist in improving the lip contour and smile is also included. Lastly, we review the most common complications during these procedures and their management.

Introduction

Lip fillers have exploded in popularity over the last decade, in part due to celebrities revealing they have had the procedure done, as well as social media helping to create more visibility surrounding the procedure.[1] In addition, there has been a movement in medicine towards preventative healthcare and treatments, so the patient population has gotten younger, expanding the number of patients seeking cosmetic treatments.[2] Not only are more and more patients getting lip filler procedures done (overall use of hyaluronic acid fillers has increased 58.4% from 2014 to 2018), but there are more injectors performing lip augmentation procedures.[3]

While this can be an extremely satisfying procedure to perform for both the injector and the patient, lip augmentation is nuanced, and includes an understanding of what ideal lips look like, as well as making sure they are harmonious with the rest of the facial features to avoid the pitfalls of overfilled and obviously augmented lips which can appear unattractive. The injector should know how to appropriately assess the patient for changes in the perioral area – including overall facial fat loss and bony remodeling – and how to address these changes. They should also understand the mechanics of how dynamic movements of the perioral area can affect the smile and its attractiveness, and how to use neuromodulators in their armamentarium when performing a lip augmentation procedure to create an ideal lower face.

The injector should also be aware of the side effects that can occur with lip fillers, including nodule formation, infection, and most importantly, the risks of ischemia, necrosis and blindness. Avoiding these complications by using proper technique and having an in-depth knowledge of anatomy is important, but will not completely eliminate the risk. As such, every injector should know how to recognize – and be prepared to manage – these complications in order to avoid any permanent sequelae for the patients.

Anatomy

Morphology

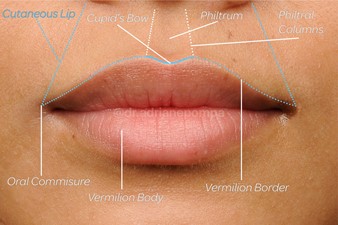

The morphology of the lips is important to understand, as the anatomical subunits should remain distinctive (Figure 1). Overfilling any of these subunits can cause distortion and an unnatural result. There are three layers to the lip, consisting of: the outer layer, including the cutaneous and vermilion border; the middle layer, consisting mainly of muscle (the orbicularis oris); and the inner layer, or mucosal membrane. The lip is subdivided into the upper and lower lip.

The upper lip borders are:

- Superiorly: the nose

- Laterally: the nasolabial folds

- Inferiorly: the mouth horizontal axis

The lower lip borders are:

- Superiorly: the mouth horizontal axis

- Laterally: the oral commissures

- Inferiorly: the mandible

The upper lip can be further subdivided into three units:

- The white lip (or cutaneous lip), medially consists of the philtrum, which has two raised vertical columns of tissue (philtral columns), and forms a midline depression (philtrum). The philtral columns are made up of the decussating fibers of the orbicularis oris.

- The dry red lip (vermilion body) is defined around its border by a fine line of pale skin circumferentially (the white roll), and is bordered superiorly and medially by the Cupid’s bow, which is a convex structure containing two paramedian elevations of the vermilion.

- The wet red lip (red roll), not readily visible unless you evert the dry red lip, ends in the oral vestibule and is defined medially by the frenulum.

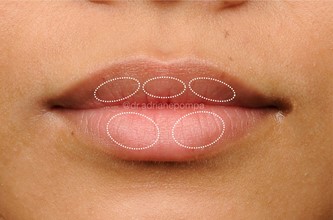

There are natural, embryological protuberances of the lip that can be designated as the aesthetic subunits. The upper lip has three, and the lower lip has two (Figure 2).[4] It is important to note that there can be natural variations in these protuberances, and they should be maintained if the shape of the natural lip is to be preserved.

Vasculature

Understanding the vasculature when rejuvenating the perioral area is vitally important because the perioral area can be deemed high risk for occlusion and subsequent ischemia or necrosis. A current study found that more than half of lip injections showed filler near the superior labial artery (SLA) or inferior labial artery (ILA), independent of injector, method, or plane of injection.[5] The facial artery gives off the branches of the labial arteries (superior and inferior) 1-2 cm lateral to the oral commissure with a high variability of course and presence.[6] It runs about 7-8mm from the vermilion border.[7] Ultrasound studies have shown that the depth of the labial artery is most frequently within the submucosal layer, followed by intramuscular, followed by subcutaneous. Other studies show a more superficial course of the SLA/ILA near the midline, whereas yet other studies have not found this to be true.[8],[9] Thinning of the lips is thought to bring the surface of the lip closer to the artery; therefore, more caution is advised in older patients and those with massive weight loss.[10]

Innervation

The sensory innervation of the lip is provided by the maxillary nerve, while the motor nerve supply is provided by the branches of the facial nerve, which includes both the temporofacial and cervicofacial nerves.[11]

Ideal Lip Proportions

Fuller lips are associated with youth and attractiveness. In facial aesthetics, lips have become a central area of focus for rejuvenation with lip augmentations becoming one of the most popular non-invasive treatments. Since 2000, female lip augmentations have increased by 43%.[12] This phenomenon has permeated social media, where overfilled and distorted lips are often depicted.

A formulaic approach to the ideal lip proportion has been difficult to define, and varies across culture and injector. An intuitive understanding of beauty by the injector will create a foundation for their aesthetic plan, and understanding the different theories about beauty and proportions will help guide a tasteful rejuvenation. Additionally, gender and ethnic differences and the individuality of a patient’s facial shape and lips should be maintained to avoid a disharmonious outcome.

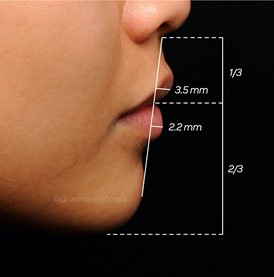

Mathematical proportions that contribute to facial attractiveness have been studied since the time of the ancient Egyptians. The study of ideal proportions with regard to the geometry of the face has been difficult to define.[13] Neoclassical facial cannons have long since been applied to facial aesthetics. Among them, the face can be divided in horizontal thirds, where the lower horizontal third is defined as the area from the subnasalae to the menton. This lower third is further subdivided into thirds, where the upper third defines the upper lip, the middle third the lower lip, and the lower third the chin. The ratio of the upper lip to the lower lip and chin should be ⅓ to ⅔ (Figure 3).[14] This proportionality varies among ethnicities and is not always reliable, so it should be used as a general guide when assessing the patient.[15] [16]

The golden ratio, or Phi (ɸ), is also known as the Divine Proportion, and is used by many injectors to define the ideal face.[17] This irrational number, 1.618033988…, is obtained when line a + b is sectioned such that a + b/a = a/b. The reciprocal of Phi is 0.618033988 (lowercase phi) and is equal to ɸ-1. Rickets first described the width of the mouth to be ɸ times the nasal width[18]. Swift and Remington popularized the use of golden calipers, a tool used for measuring the ɸ ratio, where the intercanthal distance (x) is used as the landmark for establishing the length where Phi (1.618x) and phi (0.618x) establish the aesthetic goals for an individual patient.[19]

Using these measurements, the overall width of the lip, or red vermilion show, Phi correlates with a vertical line dropped from the medial iris on either side. In Caucasian women, the ideal upper to lower lip ratio is 1:1.618. This ratio is maintained when measuring the distance from peak to peak of the Cupid’s bow, compared with the peak of the Cupid’s bow to the ipsilateral commissure. The distance between peaks of the Cupid’s bow is phi (0.618x) of the distance from the columellar base to the mid-upper lip vermilion border. On the lateral view, the upper lip should project slightly more than the lower lip. If a straight line is drawn from the subnasion to the pogonian, the upper lip should project 1.3 mm more than the lower lip, with the upper projecting 3.5mm and the lower lip projecting 2.2mm (Figure 3).[20]

Other studies have determined the ratio from the upper vermilion and the upper white lip to be most attractive at 1:1.2-1:2.3.[21] Additionally, surface area and the ratio of the lips to the lower third of the face have been found to be most ideal at a 53.5% increase in surface area from baseline, and when the lips make up 9.6% of the total surface area of the lower third of the face.[22]

Gender and ethnic differences exist among these measurements, as many studies only include Causian faces, but some are still ill-defined. Although Caucasian women and men have similar facial aging patterns in the lip and perioral area, men tend to have fewer perioral rhytides in comparison to women, due to better skin density and increased subcutaneous fat surrounding the hair follicles[23]. When enhancing male lips, the perfect Cupid’s bow, symmetry, and fullness of the medial tubercle are not as important as in the female lip, while a nice vermilion border and curved line on the profile view are preferred.[24]

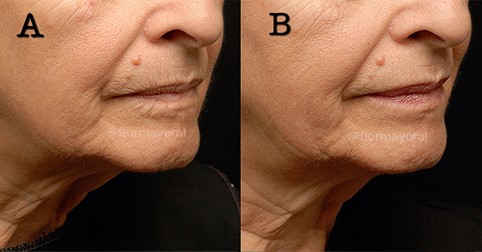

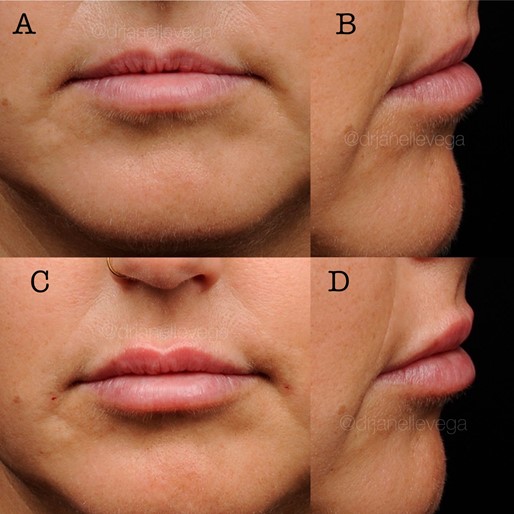

Individual differences exist between demographic, geographic and ethnic concepts of beauty, but few studies exist on elucidating these differences.[25] Heidekrueger et al., showed that country of residence, ethnic background and profession significantly impact individual lip shape preferences. Of note, plastic surgeons’ preferences differed from laypersons’.[26] Interestingly, the study’s authors found that the 1.0: 1.0 upper to lower lip ratio can be considered most pleasing across a wide range of people.[27] This is in line with the finding that the ideal phi number (1:1.618) approaches 1:1 in Asian and African American lips. The author’s experience is that Hispanic patients’ lips can fall into either proportion, depending on the baseline morphology (Figures 4,5). There is a paucity of data regarding the lip preferences of Hispanics. The authors believe that in light of this varied data, clear communication between the injector and the patient is critical to managing patient expectations and achieving a desirable result based on each individual’s understanding of beauty.

Aging of the Lips and Perioral Area

When planning a lip augmentation, it is critical to remember that the lips play a central role in the perioral area, which may also require rejuvenation depending on the patient’s age. As we age, fat and bone loss create a shadow around the lips. Failing to address these areas and choosing to augment only the lips will further emphasize this shadow and lead to a “mismatch” between the lips and surrounding area, which may be perceived as fake and/or odd to the untrained eye.[28]

As we age, fat loss occurs within the vermilion lip itself, the vermilion border and the cutaneous lip, resulting in contour changes of both the upper and lower lips, as well as perioral rhytids.[29] The dermis of the lip has also been shown histologically to decrease in thickness with age, demonstrating fragmentation of collagen and elastin, which is worsened by photoaging. This can contribute to a superficial wrinkling of the lips that occurs over time.[30] Muscle atrophy of the orbicularis oris also ensues, most evidently in the vermilion border, likely contributing to the loss of anterior projection and “pout” that occurs with age.[31] Dynamic wrinkles form perpendicularly to the muscle fibers of the orbicularis oris around the mouth from repetitive movement, which eventually leads to static wrinkles.[32] The combination of these processes results clinically in thinning of the lips, elongation and flattening of the upper lip, loss of the Cupid’s bow, loss of definition between the vermilion and cutaneous lip, decreased show of the wet-dry border and decreased anterior projection of the lip, as well as static and dynamic wrinkles which are characteristic of senile lips.[33]

As previously mentioned, it is essential to consider changes occurring in the perioral area when planning a lip augmentation. The stigmata of facial aging in this area occurs from a combination of facial fat loss, skeletal remodeling, increased laxity, soft tissue repositioning and hyperdynamic movements, as well as extrinsic factors such as photodamage and smoking. In the midface, maxillary bone resorption, especially around the piriform aperture, contributes to a posterior positioning of the nasolabial fold and the upper lip.[34],[35] The nasolabial fold also deepens as a result of a ptotic superficial musculoaponeurotic system (SMAS) and skin, allowing the folding over of malar fat. Repetitive contractions of the lip elevators during nose wrinkling also contribute to a deepening nasolabial fold.[36] The lip-chin crease becomes more evident as a result of a combination of loss of submentalis fat, mandibular bony support and hyperactivity of the mentalis. This muscle movement can also lead to a peau d’orange (orange peel) appearance of the chin, where the superficial SMAS attachments become visible, creating dimpling rhytids.[37] [38] A loss of support in the alveolar ridge from tooth loss and mandibular bone loss contributes to loss of support for the lips and jowling, respectively.[39] Marionette lines, the vertical lines coming down from a downturned oral commissure, also begin to form from hyperdynamic muscle movement, giving an overall sad expression.[40] This is all worsened by volume loss, a loosened skin envelope and photodamage. Addressing these changes as an adjunct to correcting the changes in the lips is essential for a harmonious rejuvenation.

Consultation

When seeing a new patient consultation for a lip augmentation procedure, a thorough history should be taken of prior lip procedures, including fillers (and type), surgical treatments (lip lifts, resection of product, skin cancer surgeries, cleft lip repair), history of facial palsies, placement of permanent fillers, history of piercings through the lip, history of herpes simplex virus (HSV) and a history of any adverse events having occurred during treatment. Adverse events include a history of occlusion, sensitivity to a specific injectable filler, or nodule formation. This will help the clinician determine if the patient is a good candidate for a lip augmentation, assist with planning a combination filler/neuromodulator treatment, and avoid any untoward side effects by being aware of potential pitfalls.

Setting goals and expectations is also an important part of an initial or follow-up consultation. It is important to get a sense of a patient’s aesthetic ideals and goals – oftentimes, they will have photos of celebrities or lips they have seen on social media that they would like to emulate or approximate in shape. The authors find this visual gauge useful in counseling the patient on whether or not this is a realistic goal for their particular lip shape or for their facial and/or lip proportions, and to give an accurate estimate of how many syringes and type of product needed to achieve a positive result. Getting on the same page – visually speaking – is important, as the patient’s idea of what is natural looking and the injector’s idea of this may not match up.

Recognizing patients who may have an unhealthy obsession with their appearance should also be a part of the consultation process. Although the prevalence of body dysmorphic disorder (BDD) is 1 -2% in the general population, it is much higher in patients presenting for cosmetic procedures (as high as 6 – 15% of patients). Learn to recognize the signs that your patient may be suffering from BDD, such as having had multiple procedures with many different injectors, expression of dissatisfaction with each procedure, obsession with lip augmentation when their lip size is already large or a fixation on imperceptible imperfections. It may be best to avoid procedures for these patients and instead refer them for psychiatric evaluation to confirm your suspicion of the diagnosis and assistance with its management.[41], [42]

Equally important is the review of post-procedure care so that the patient is aware of what is a normal reaction, when they should call their provider, and things they should avoid after the procedure (Table 1).

| Post-procedure care for lip augmentation |

| Swelling is an expected side effect, and can last up to 7 – 10 days. Contact your injector if your swelling is extreme or lasts longer than this time frame. |

| Bruising is a common side effect. Contact your provider if you have significant pain or bruising after the procedure, or if your bruising is mottled. |

| We advise patients to refrain from exercise for 48 hours after the procedure. |

| Intermittent icing – 10 minutes at a time – can help with the swelling. |

| Avoid dental appointments for at least one week after the procedure. |

| Alert your provider if you have significant pain, swelling, redness, bump formation, oozing or reactivation of a cold sore after your procedure. |

| Avoid pushing or pressing on the area unless directed by your injector, as this can trigger more swelling. |

The physical assessment of the lips should begin during the consultation portion, where it is helpful to observe the patient’s lips in a dynamic state of natural speaking to help gauge any musculoskeletal issues and asymmetry that can be addressed with the use of neuromodulators.[43] A formal assessment should follow, both at rest (front and profile view) and during animation, which should include puckering, smiling (with/without teeth) and grimacing, keeping in mind ideal lip proportions and how they apply to the patient. The evaluation should include assessments of all major landmarks of the lips and perioral area for volume, symmetry, inversion of the vermilion and visualization of the gingiva when smiling.[44] Neuromodulators can assist in correcting some of the asymmetries when smiling or puckering and are reviewed in a later section.

As discussed in Aging of the Lips and Perioral Area, the downward shift of the midface from facial fat loss, loss of elasticity and recession of bone contributes to an aged appearance and shadowing of the area around the lips, and should be addressed to create an optimal and balanced rejuvenation congruent with the lips.

The patient’s dentition, orthodontics, angle of teeth and dental occlusion can also affect how the overlying lips appear. When a patient has had extensive dental loss, for example, the underlying bony support is diminished, leading to a more collapsed appearance of lips.[45] Correction of these issues with a dental specialist can assist in the appearance of a more attractive soft tissue profile and contour. Issues with dental occlusion, such as retrognathia, can also give an appearance of a pseudo augmented upper lip, which should also be considered prior to injection.[46]

Injection Approaches

Needle

Despite an abundance of scientific literature on the topic, there is no standardized approach to the safest way to inject lip fillers. Many techniques rely on certain assumptions and findings. Since the labial arteries have been found to run mostly in the deep submucosal plane, the authors recommend staying in a more superficial submucosal plane or subcutaneous plane. Because of this, use of a small particle hyaluronic acid is preferred as it gives less Tyndall effect and blends better in this area. The Tyndall effect in aesthetics refers to the bluish discoloration that is visible within the skin secondary to superficial placement of hyaluronic acid. It is caused by visible light scattering when it enters a non-homogeneous medium, allowing only the shorter wavelengths (blue light) to scatter and be visible to the observer.[47],[48] Careful initial evaluation is important when planning a technique on a particular patient. It is also important to take note of asymmetry, need for projection versus augmentation or both, and vermilion border correction. A fine gauge (30 x ½ inch) needle is preferred and injection should occur 30 degrees parallel to the length of the lip.

Various types of needle injection techniques have been described, and they include linear threading, fanning, serial puncture, and cross-hatching.[49] Vermilion border correction can be performed with a retrograde threading technique. Another technique is to place the needle at 0.5-1mm from the vermilion border, in the red lip, and watch the product travel along the white roll. It allows for less trauma and more precise placement of the product. Massage after injection is recommended to ensure the product travels along the white roll plane. It is important not to place the filler into the cutaneous portion of the lip, or overfill this area. This will lead to obliteration of the normal anatomical area and elongation of the upper lip. Typically, 0.05 to 0.1 mL per ¼ of the vermilion border of the lip should suffice (Video 1).

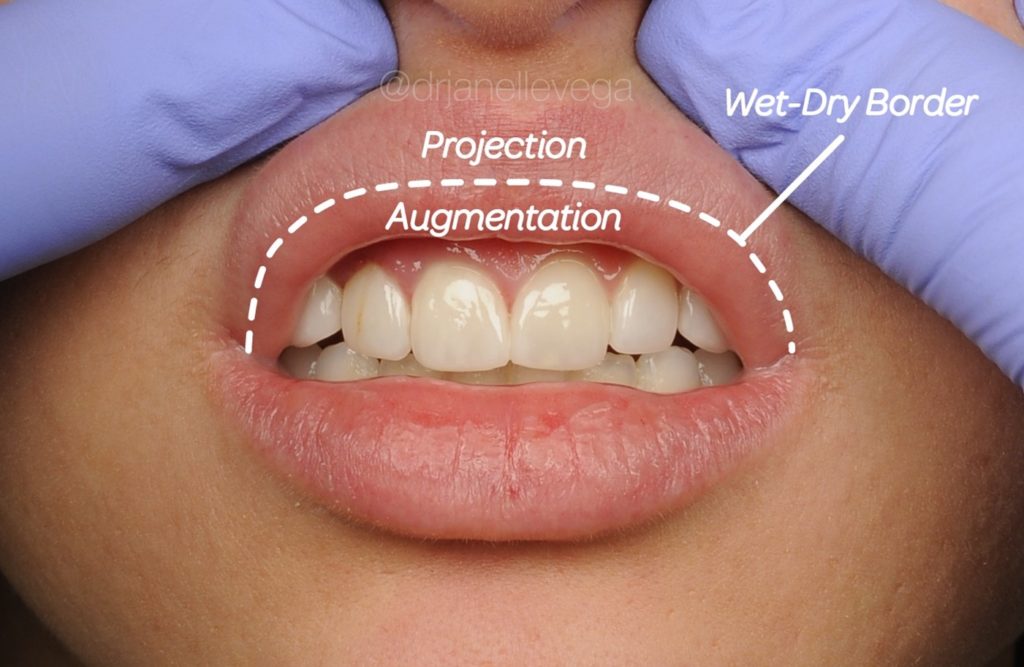

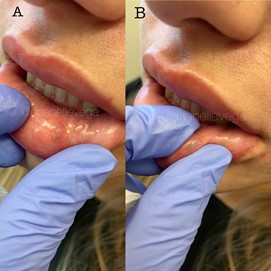

The vermilion body should be injected with maintenance of the existing aesthetic subunits, or tubercles. The authors also perform this injection via retrograde threading or retrograde fanning technique, from medial to lateral, ensuring to place enough traction for rapid, less painful insertion. In the event of projection, the injection should take place in the dry red lip (Video 2). If the intended end point is augmentation, the injection should take place in the junction of the dry and wet red lip (Video 3). It helps to visualize the wet/dry junction by placing pressure on the vermilion body, creating better eversion and visualization of the wet/dry junction and isolating the space you want to place the filler for augmentation (Figure 6). If resistance is met, then the needle should be redirected. Injections should be done slowly, pressure maintained evenly, and the injector should be aware of any pain out of the ordinary or color changes. With each section, palpation of the area injected should be performed and a slight massage of the filler should be done if there is a lack of uniformity. If significant bruising occurs, then it is recommended to stop injecting that area as edema can obscure the intended aesthetic outcome. Waiting 1-2 weeks and then reinjecting is preferred.

It is relevant to note the tenting technique that has become popularized as of late. This method consists of injecting from the cutaneous lip into the red lip using a serial retrograde threading technique in vertical columns. In the author’s experience, this should be reserved for only advanced injectors as the cutaneous lip can become overfilled and/or migration of product can be seen over time.

The philtral columns are commonly injected in this area. The authors maintain this area should be reserved for elderly patients who have lost volume in this area, versus in a youthful perioral rejuvenation. In the correct patient, this can be achieved by a retrograde threading technique, entering at the G-K point (peak of the Cupid’s bow) and pointing the needle vertically toward the base of the nose, where the philtral columns end.

For perioral rhytides, a combination of hyaluronic acid filler and neurotoxin are recommended. For the injection technique, the authors prefer serial puncture for each line perpendicular to the line in a superficial plane. Asking the patient to blow a kiss can aid in showing which lines should be filled. In some patients where the rhytids extend into the dry red lip, the vermilion border should also be augmented for a more optimal result (Figure 7, Video 4).

Cannula

Using a blunted microcannula when performing a lip augmentation, versus using a needle, has several advantages. There are fewer puncture sites, allowing the injector to complete an entire lip augmentation using only 1 – 2 entry points, reducing the risk of bruising, trauma and edema. Patients also report less pain when getting fillers with a cannula, versus a hypodermic needle.[50] In cadaveric studies of injection of cannula versus needle, microcannula injections also tend to create a more uniform deposition of filler, although these results were not statistically significant.[51] Because the cannula is flexible and features a blunted tip, there is an increased factor of safety as the cannula is more likely to circumvent a vessel than pierce through it. However, there have been reports of arterial wall perforations and emboli even with a cannula. Caution is advised when using smaller gauge cannulas, which can act similarly to needles (27, 30g), as well as when there is resistance to the cannula passing through the tissue. In the case of resistance, the artery may be bound by fibrous septae, increasing risk of penetration of arteries. It is recommended that the injector reinsert the cannula and find an area of low resistance to avoid this.[52] Always maintain safety protocols and observe how the patient is doing throughout the procedure, irrespective of the method of injection.

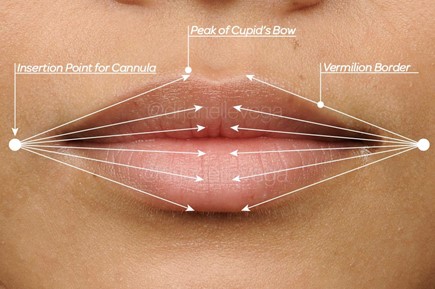

For lip augmentation procedures, the authors prefer a cannula size of 25 or 27 gauge, and 1.5 inches in length. The entry point is placed 1 – 2 mm lateral to the oral commissure (Figure 8). The needle size should be one gauge larger than the cannula. For a 25 gauge cannula, a 23 gauge needle or larger is used to create a port, and for a 27 gauge cannula, a 25 gauge needle or longer should be used to create a port of entry. Some injectors prefer to place injected lidocaine at the entry point for the needle; however, this is optional. The port should be created using an approximately 15° angle – gentle rotation of the needle at the port of entry without burying the needle deeper (to avoid vessel penetration) helps the entry point stay patent for cannula entry.

The cannula should then be primed with product and inserted at the same angle as needle entry was made, and advanced using a rotary motion. If you are augmenting the vermilion border, direct the cannula in a rotary motion to guide it along the border until you reach the peak of the Cupid’s bow, and place 0.5 – 1 mL in a retrograde threading motion as you retract the cannula. Take care to stop injecting prior to reaching the oral commissure to avoid inadvertently augmenting this area.

For the body of the lip, begin by determining the goal of your lip injection procedure. For creating more projection in the lip, the cannula should be directed within the submucosal plane between the white roll and the wet-dry border, and advanced using a rotary motion (Figure 9). The product can be placed using a retrograde fanning technique or small boluses as needed for contour correction. If your goal is augmenting the lip, then the cannula should be directed inferior and deep to the red roll, and the product can be placed using a retrograde fanning technique or small boluses (Figure 10, Video 5).[53] As previously mentioned, if there is ever any resistance to passage of the cannula, the cannula should be removed and redirected so as to avoid unnecessary trauma and/or perforation of blood vessels. This process should be repeated for all four quadrants of the lip, which can be reached using two entry points on either side of the lip (Figure 8).

Video courtesy of Dr. Janelle Vega

Video courtesy of Dr. Janelle Vega

Neuromodulators

Gummy Smile

Neuromodulators compliment – and take a back seat to – lip and perioral rejuvenation with fillers. Their need becomes apparent when assessing the patient at rest and during animation, including smiling and puckering. On animation, one should look for asymmetry, excessive inversion of the vermilion, and prominent gingiva (Figure 11).[54]

A normal smile can be defined as a 1-2 mm gingival display, measuring between the gingival margin of the maxillary central incisors and the inferior border of the upper lip[55] “Gummy smile” refers to excessive gingival show of >3mm when smiling, and can be categorized several ways.

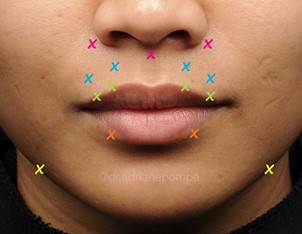

Mazucco et al. first subclassified the gummy smile into 4 components: anterior (>3mm gum show between the canine teeth, due to the levator labii superioris alaeque nasi [LLSAN]), posterior (>3mm of gum is exposed only posterior to the canines, due to activity of zygomatic muscles), mixed (>3mm gum exposure in both the anterior and posterior regions, due to action of both muscles), and asymmetric (excessive gum show on one side caused by contraction of either LLSAN, zygomaticus, or both).[56]

De Maio et al. classify gum show as moderate or severe. A moderate gummy smile occurs when the levator labii superioris alaeque nasi muscle elevates and everts the upper lip, while the depressor septi nasi muscle draws the nasal tip downward and lifts the medial tubercle. A severe gummy smile recruits, in addition, the levator labii superioris and zygomaticus minor muscles to raise the upper lip.[57]

The classification is not as important as understanding that there are different muscles that cause different types of lip show. Patient selection is crucial, as overtreatment could lead to lip ptosis and elongation of the upper lip. This makes patients with a short upper lip better candidates.[58] The total dose should be equivalent to 5-10 units of onabotulinum toxin, depending on type, severity and asymmetry.

The authors have found that using the technique of a lip flip, discussed below, can help correct the gummy smile by everting the lip, therefore covering part of the gum show in the same manner as an augmentation, but to a lesser degree. These techniques are advanced and should only be used if you have an intimate understanding of the facial musculature anatomy. It is better to start with lower dosing and add more at the two-week follow up (Figure 12).

Perioral Rhytides and “Lip Flip”

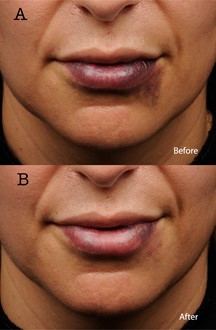

Perioral lines can be treated with both toxin and hyaluronic acid. Neuromodulators in this area help with deep lines worsened by lip pursing.[59] The orbicularis oris is the main muscle in this area and the superficial fibers are responsible for lip pursing.[60] There are two points of injection for each side of the upper lip and one point of injection for each side of the lower lip for a total of 5-7 units of – or the equivalent of – onabotulinumtoxin A (more on upper than lower). It is important to stay 1 cm medial to the oral commissure to avoid diffusion into the modiolus.[61] Patients should be warned of the possible effect on speech when pronouncing hard letters like “P,” difficulty playing certain musical instruments, using a straw, smoking, or singing. Excessive dosing can also lead to drooling, flattening of the lip and flattening of the Cupid’s bow if injected too medially in the upper lip.[62],[63] A combination of HA and neuromodulators in this area have been shown to be safe and effective (Figure 13).[64]

There are a limited number of studies on the “lip flip.” This is an increasing trend where in a similar technique to perioral lines, the orbicularis oris is injected with botulinum toxin-A, but only in the upper cutaneous lip. The injection is placed closer to the vermilion of the lip to specifically target the intrinsic portion of the muscle, which is made up of a single or double band of fibers that start at the modiolus and curls upon itself, forming the vermilion border.[65] By relaxing this muscle, the upper lip rolls out and appears fuller. The authors feel this compliments hyaluronic acid filler injections, and anecdotally helps prolong the effect of HA fillers in the lip. It is often preferred by young patients who are seeking a slight improvement without injecting a hyaluronic acid filler.

DAO: Depressor Anguli Oris Muscle

Many patients come for initial treatment when they feel they look mad or sad at rest. This is in part due to the excessive contraction of the DAO, which draws the corners of the mouth down. It is a superficial muscle that starts at the angle of the mandible, and becomes narrower superiorly, merging into the modiolus. It is important to note that the depressor labii inferioris (DLI) is partially covered by the DAO, and blends into the orbicularis oris.[66] Treatment consists of 2-4 units of onabotulinum toxin, or equivalent units of, at the jawline, at least 1 cm away from the corner of the mouth, on each side of the face. Injectors should be cautious not to inject too medially, as this could result in diffusion to the DLI, causing an asymmetrical smile.[67] Using 3D facial anatomic references and landmarks, Choi et al. recommend DAO injections be performed at depths of 6.3mm in females and 7.3 mm in males (Figure 14).[68]

Complications and Management

The increase in popularity and prevalence of lip augmentation procedures over the last several years has resulted in more providers with varying levels of expertise performing this procedure. This procedure is safe under the right circumstances, but there is always a risk of complications, ranging from mild discomfort and bruising to more severe complications including infections and occlusion of arteries with subsequent tissue necrosis. All cosmetic injectors should be aware of these risks, know how to recognize them and be knowledgeable in how to manage them.[69]

Pain

Pain or discomfort is common during lip filler procedures. This can be minimized with the use of topical anesthetic, nerve blocks, ice, the use of small gauge needles, blunt cannulas, inhaled nitrous oxide,[70] vibratory devices[71] and/or the use of products that contain lidocaine. Post-procedure discomfort can usually be managed using a combination of ice and/or acetaminophen or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications (NSAIDs).[72] If a patient is experiencing pain out of proportion to the procedure either during or after the procedure, this could be the harbinger of a more serious complication, such as a vascular occlusion, and should be heeded.[73]

Bruising

One of the most common complications of lip augmentation procedures is developing ecchymoses (bruising) at the site of injection, which generally resolves over 7 – 10 days. This is more common when using a threading or fanning technique with a needle when working in the submucosal plane, and this side effect can be partially reduced with the use of a cannula for injection, instead of a needle. Injecting slowly, using small aliquots of product, and using compression upon development of a bruise also helps to minimize the appearance of a hematoma.[74] If a patient is on anticoagulant therapy, antiplatelet therapy, NSAIDs, or certain vitamins and herbal supplements (Vitamin E, ginseng, ginkgo biloba, garlic, kava kava, celery root, or fish oils), these should be discontinued 7 – 10 days prior to the procedure after consulting with their primary care provider to reduce the risk of bruising.[75] Avoidance of exercise post-procedure for 24 hours is also thought to minimize this complication. Cold compresses, vitamin K creams, arnica (prophylactically and post-procedure), and aloe vera have also been used to treat bruising post procedure with varying degrees of success.[76] The clinician may also use a vascular laser (such as a pulsed-dye laser) with minimal risks and downtime to aid in resolution of purpura in patients who prefer a quicker resolution for the purposes of cosmesis (Figure 15).[77]

Edema

Swelling, or edema, is a common side effect of all fillers, but it can be especially noticeable following a lip augmentation. This side effect is expected, temporary and can start within minutes to hours of the procedure. The duration and severity will depend on several variables, including the type of product and amount used, as well as patient risk factors (such as dermatographism). This will typically resolve within several days, but can also be managed with oral antihistamines and/or oral corticosteroids (0.5 – 1mg/kg/day x 3 days).[78] [79]

Rarely, patients may develop angioedema following hyaluronic acid fillers, which is considered an immediate-type hypersensitivity reaction.[80] This systemic reaction must be quickly recognized and managed as it can involve the airway in some patients and proceed to anaphylaxis. For these occasions, it may be judicious to have an epinephrine injection available as part of your injection arsenal.[81] [82]

Delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction (cell-mediated) can also occur, from one day to several months after injection. This is characterized by induration, redness and swelling, and is unresponsive to antihistamines. The best course of action is removal of the filler with hyaluronidase to remove the offending antigen.[83] [84]

Nodule formation

Nodules are by far one of the most common issues arising from filler injections, and are often seen after lip augmentations. In general, they can be classified by their type (noninflammatory, inflammatory, infectious) and their onset (early, late, delayed). When nodules present within several days to weeks, this is usually related to technique and includes poorly placed product or acute infection related to not using an aseptic technique. Later presentation of nodules is more commonly related to the product itself or how the patient’s immune system interacts with the filler, and includes the development of biofilm and/or granulomas.[85] [86]

With suboptimal filler placement or too much filler in one area, the patient can develop visible implants and palpable nodules. Superficial placement of the material is often the main issue and this is related to technique. If massage does not correct the issue, then the injector can consider drainage after wound incision with an 11 blade, needle aspiration, as well as hyaluronidase to dissolve the excess product (Figure 16).[87]

Delayed onset nodules can appear weeks, months or years after injection, and are most commonly related to the formation of granulomas, a focus of chronic inflammation which is a product of host reaction to the filler, which occurs at a rate of 0.01% to 1%.[88] This can appear as red, indurated papules or plaques, sometimes with drainage. Granuloma formation has been attributed to the amount of product, impurities, irregularities of injected material, and biofilms are now thought to play a role in their formation as well, which will be discussed in the infection portion. Treatment of granuloma formation includes hyaluronidase to remove any residual product, intralesional and/or oral corticosteroids, intralesional injection of 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), and excision in cases where all else has failed.[89] [90] [91] Oftentimes, these patients are also treated with antibiotics, especially in recurrent cases where biofilms are thought to play a role.[92]

Infection

It is unusual to develop acute infections from the use of injectables.Infections usually occur from a failure to properly prepare the skin prior to injection, resulting in contamination of the injection site. Any break in the skin barrier will create a risk of infection because a portal of entry has been created for microbes to enter through, including bacterial, viral and fungal infections.[93] When there is the presence of a foreign body, such as a filler, clinical infection also occurs more easily because the bacterial load required to cause infection is much lower.[94] Therefore, aseptic technique should always be used during this medical procedure.[95]

If the patient develops an acute erythematous or tender nodule, this is a sign that they may have developed an abscess. If it is fluctuant, incision and drainage should be performed and the material sent for aerobic (including mycobacterial) bacterial, anaerobic bacterial and fungal microscopy and culture. Results should be monitored for 3-4 weeks.[96] The injector should also consider the use of hyaluronidase to remove the product, which has not been shown to clinically worsen infection in an abscess. In the case of cellulitis, which can also occur, it is not recommended that the clinician use hyaluronidase because of the risk of infection spread – and adding oral antibiotics is warranted.[97]

The most common offending pathogens in these cases are Staphylococcal or Streptococcal species which are usually present as part of the skin flora (Staph. Aureus or Strep. pyogenes). First-generation cephalosporins will usually be sufficient; however, if methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus is suspected, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and rifampin should be considered.[98]

When abscesses have a delayed presentation (>2 weeks after procedure), the injector should consider an atypical mycobacterial infection which has been reported from infected water sources (from the use of ice cubes, infected faucets), as well as with medical tourism. These mycobacterial infections may require prolonged, multi-drug therapy and be resistant to standard treatment (M. abscessus, chelonae and fortuitum are the most commonly reported).[99]

Biofilms are composed of densely packed bacterial colonies protected by secreted polysaccharides, which help them to evade the immune system and resist antibacterial treatment.[100] They are thought to play a role in the formation of delayed nodules and granulomas. Although they are composed of 95% bacteria, traditional culture is often difficult, and tissue culture, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) analysis are often needed to assist in diagnosis of bacterial strain involved.[101] Clinically, it can be difficult to differentiate biofilms from granulomatous reactions and they are managed similarly. Recurrent, suppurative granulomatous inflammation after treatment and improvement of granulomas can be a signal of biofilm reactivation.[102] In addition to treatment with hyaluronidase, intralesional corticosteroids, intralesional 5FU, the addition of long term antibiotic therapy, including newer-generation macrolides, as well as quinolones, is an important adjunct.[103]

Herpes

When herpetic recurrences occur, they are most likely to occur in the perioral area, nasal mucosa, or the mucosa of the hard palate.[104] In patients with a history of recurrent herpes labialis, reactivation can be triggered by a lip augmentation procedure. Prophylactic treatment with valacyclovir (1gm/day) for one day prior to – and three days after – the procedure will help with preventing recurrence.[105] If a patient has an active infection, however, then the procedure should be delayed until complete resolution. It is important to distinguish a blistering reaction as a result of vascular compromise from a herpes simplex virus (HSV) recurrence.

Migration

Filler migration can occur, and as a consequence, create an undesired contour of the lips. This is often technique related, where too much volume is placed in a certain area, or too high a pressure is used when injecting, causing filler overflow to an adjacent area with less resistance. Fillers placed in an area with high muscle movement (such as the orbicularis oris) can also create shifting of product to undesired locations. While massaging the product can be helpful for shaping and for smoothing nodules, over-vigorous massage by the injector and/or the patient can also contribute to product migration. In the case of permanent fillers, migration can be seen from gravity or phagocytosis of the product from macrophages, and redepositing of material elsewhere, as well as lymphatic spread. Hyaluronidase can be used in these cases to correct the unwanted contour and restore a more natural lip proportion (Figure 17).[106] [107]

![Figure 17 (A,B,C,D): The patient shown previously had a lip augmentation at another clinic and was unhappy with the excess fullness of the cutaneous upper lip (Figure 17 A,B). This result can be caused by technique and/or product choice. The patient is shown (Figure 17 C,D) one week post-treatment with hyaluronidase in the upper cutaneous lip to restore her natural lip contour. The half-life of hyaluronidase is short at just two minutes, but the duration of action is seen up to 48 hours post injection.[108] Therefore it is the recommendation of the authors that injectors wait between 3 - 7 days before reinjection of hyaluronic acid to avoid unwanted dissolution of fillers. Photos courtesy of Dr. Janelle Vega](https://www.rejuvenationresource.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/lip-fillers-chapter-24.jpg)

Ischemic events/Necrosis

Arterial occlusion, or compression with subsequent tissue ischemia and necrosis, is a well known and feared consequence of lip augmentation procedures and can occur when filler is inadvertently placed in a blood vessel or the blood vessel is compressed from excess filler. Blindness is also a feared complication that, although rare during a lip augmentation, can occur because of the powerful anastomotic network between internal and external carotid arteries.[109]

Introducing risk-minimizing strategies to your practice can help reduce this occurrence. A deep understanding of the anatomy of the lip vasculature and how it relates to your injection technique and location is the most important step in avoiding this. However, anatomic variation in vasculature is known to occur, even within the same patient on contralateral sides. Therefore, avoidance of arterial occlusion cannot be guaranteed by knowledge of anatomic landmarks alone.[110] Blunt cannula use during a lip augmentation procedure minimizes this risk to some extent (especially when using larger gauge cannulas), because instead of penetrating through the artery, the blunted cannula can circumvent the vessel.[111] Avoid high pressure injections, such as can occur inadvertently when there is a blockage in the needle. If the injector feels too much pressure when attempting to place filler, it is best practice to stop injection and clear the needle before continuing to avoid dislodging the blockage and delivering a large bolus. The more product enters the vascular system, the more dire the consequences and the more severe the side effects.[112] Constant movement of the needle and/or cannula is also recommended to avoid placing too much volume in one area. Aspiration is also a good habit to help avoid intravascular injection, but not aspirating blood does not guarantee that you are not in a blood vessel – and it becomes especially unreliable when the injector is using thicker gels combined with smaller needles.[113]

Recognizing signs of an occlusion is essential because acting quickly in terms of treatment can prevent permanent tissue loss. Following an occlusive event, transient blanching may be seen (proximal or distal to the area of injection), followed by a livedoid pattern, which can occur over the course of minutes to hours. Livedo may be distinguished from purpura by blanching. Tissue damage can occur adjacent to the treated area and it may present with redness, inflammation and slow capillary refill (Figure 18). When the tissue has lost oxygenation for an extended period, it can look grayish-white, develop blistering, tissue loss and scarring (Figure 19). Complaints of pain out of proportion to normal or complaints of a painful bruise should be heeded as possible symptoms of an occlusion by the injector and staff.[114] [115]

First line treatment when a suspected occlusion occurs is to stop injection with filler immediately, and commence with the injection of hyaluronidase in the area of concern. Hyaluronidase is a protein enzyme used to degrade hyaluronic acid, and different formulations are available on the market. It is FDA-approved to enhance drug diffusion in tissues, and its use to treat occlusion or suspected occlusion is off-label.[116] In the authors’ opinion, this should be an essential part of every injector’s armamentarium and always available on hand when performing injections. Although hypersensitivity reactions to the product have been reported (1 in 1000 cases), a skin test is not necessary in an emergency situation such as an occlusion. It is recommended to flood the area with at least 200U. Because the enzyme can pass through fascial planes as well as vessel walls, you can inject about 3 – 4 cm apart in areas demonstrating ischemia and massage. It acts quickly to break up the product and allow reperfusion, but if no improvement is seen within 60 minutes, the provider should reinject more hyaluronidase. The clinical endpoint is reperfusion of the tissue as evidenced by the resolution of erythema, livedo, and/or blanching.[117]

Additional treatment measures are aimed at improving circulation and oxygenation and include warm compresses, vigorous massage to break any filler embolus, hyperbaric oxygen treatment to help tissues with healing, and the addition of oral aspirin, oral steroids, low molecular weight heparin and sildenafil. The use of topical nitroglycerin paste is controversial.[118] Once the suspected occlusion is resolved, traditional wound care should commence, along with monitoring for secondary infection and treatment of scarring if necessary after healing is complete. For improved outcomes, diagnosis and treatment should occur within 24 hours; delay increases the risk of tissue loss, ulceration and subsequent scarring.[119]

[1] Tijerina JD, Morrison SD, Nolan IT, Parham MJ, Richardson MT, Nazerali R. Celebrity Influence Affecting Public Interest in Plastic Surgery Procedures: Google Trends Analysis. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2019 Dec;43(6):1669-1680.

[2] Mannino GN, Lipner SR. Current concepts in lip augmentation. Cutis. 2016 Nov;98(5):325-329.

[3] The American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery’s Cosmetic Surgery National Data Bank: Statistics 2018. Aesthet Surg J. 2019 Jun 21;39(Suppl_4):1-27.

[4] Sarnoff DS, Gotkin RH. Six steps to the “perfect” lip. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11(9):1081-1088.

[5] Ghannam S, Sattler S, Frank K, et al. Treating the lip and its anatomical correlate in respect to vascular compromise. Facial Plast Surg. 2019;35(2):193-203.

[6] Samizadeh S, Pirayesh A, Bertossi D. Anatomical Variations in the Course of Labial Arteries: A Literature Review [published correction appears in Aesthet Surg J. 2019 Nov 13;39(12):NP555]. Aesthet Surg J. 2019;39(11):1225-1235.

[7] Baudoin J, Meuli JN, di Summa PG, Watfa W, Raffoul W. A comprehensive guide to upper lip aesthetic rejuvenation. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2019;18(2):444-450.

[8] Cotofana S, Pretterklieber B, Lucius R, et al. Distribution pattern of the superior and inferior labial arteries: impact for safe upper and lower lip augmentation procedures. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;139(5):1075-1082.

[9] Cotofana S, Alfertshofer M, Schenck TL, et al. Anatomy of the superior and inferior labial arteries revised: an ultra- sound investigation and implication for lip volumization. Aesthet Surg J. 2020;40(12):1327–1335.

[10] Papadopoulos T. Commentary on: Anatomy of the Superior and Inferior Labial Arteries Revised: An Ultrasound Investigation and Implication for Lip Volumization. Aesthet Surg J. 2020;40(12):1336-1340.

[11] Baudoin J, Meuli JN, di Summa PG, Watfa W, Raffoul W. A comprehensive guide to upper lip aesthetic rejuvenation. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2019;18(2):444-450.

[12]Cosmetic Surgery National Data Bank Statistics. Aesthet Surg J. 2016;36(suppl 1):1-29.

[13] Atiyeh BS, Hayek SN. Numeric expression of aesthetics and beauty. Aesthet Plast Surg 2008;32:209-16.

[14] Prendergast PM. Facial proportions. In: Erian A, Shiffman MA, editors. Advanced surgical and facial rejuvenation. Ber- lin Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag; 2012.

[15] Farkas LG, Hreczko TA, Kolar JC, et al. Vertical and hori- zontal proportions of the face in young adult North American Caucasians: revision of neoclassical canons. Plast Reconstr Surg 1985;75:328-38

[16] Farkas LG, Forrest CR, Litsas L. Revision of neoclassical facial canons in young adult Afro-Americans. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2000 May-Jun;24(3):179-84

[17] Bashour M. History and current concepts in the analysis of facial attractiveness. Plast Reconstr Surg 2006;118:741-56.

[18] Ricketts RM (1982) The biologic significance of the divine proportion and Fibonacci series. Am J Orthod 81:351–370

[19] Swift A, Remington K. BeautiPHIcation™: a global approach to facial beauty. Clin Plast Surg. 2011 Jul;38(3):347-77.

[20] Sarnoff DS, Gotkin RH. Six steps to the “perfect” lip. J Drugs Dermatol 2012;11:1081-8

[21] Raphael P, Harris R, Harris SW. Analysis and classification of the upper lip aesthetic unit. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;132(3):543‐551.

[22] Popenko NA, Tripathi PB, Devcic Z, Karimi K, Osann K, Wong B. A quantitative approach to determining the ideal female lip aes‐ thetic and its effect on facial attractiveness. JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2017;19(4):261‐267.

[23] Sarnoff DS, Gotkin RH. Six steps to the “perfect” lip. J Drugs Dermatol 2012;11:1081-8

[24] De Maio M. Fillers. In: de Maio M, Rzany B, eds. The Male Patient in Aesthetic Medicine. New York, NY: Springer; 2009:149-174

[25] Broer PN, Juran S, Liu YJ, et al. The impact of geographic, ethnic, and demographic dynamics on the perception of beauty. J Craniofac Surg. 2014;25(2):e157-e161

[26] Heidekrueger PI, Szpalski C, Weichman K, et al. Lip Attractiveness: A Cross-Cultural Analysis. Aesthet Surg J. 2017;37(7):828-836.

[27] Heidekrueger PI, Juran S, Szpalski C, Larcher L, Ng R, Broer PN. The current preferred female lip ratio. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2017;45(5):655-660.

[28] Lam SM, Glasgold R, Glasgold M. Analysis of Facial Aesthetics as Applied to Injectables. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015 Nov;136(5 Suppl):11S-21S.

[29] Rohrich RJ, Pessa JE. The anatomy and clinical implications of perioral submuscular fat. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124:266–271.Rohrich RJ, Pessa JE. The anatomy and clinical impli- cations of perioral submuscular fat. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124:266–271.

[30] Penna V, Stark G-, Eisenhardt SU, Bannasch H, Iblher N. The aging lip: a comparative histological analysis of age-related changes in the upper lip complex. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009 Aug;124(2):624-628.

[31] Ramaut L, Tonnard P, Verpaele A, Verstraete K, Blondeel P. Aging of the Upper Lip: Part I: A Retrospective Analysis of Metric Changes in Soft Tissue on Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019 Feb;143(2):440-446.

[32] Ali MJ, Ende K, Maas CS. Perioral rejuvenation and lip augmentation. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2007 Nov;15(4):491-500.

[33] de Maio M, Wu WTL, Goodman GJ, Monheit G; Alliance for the Future of Aesthetics Consensus Committee. Facial Assessment and Injection Guide for Botulinum Toxin and Injectable Hyaluronic Acid Fillers: Focus on the Lower Face. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017 Sep;140(3):393e-404e.

[34] Mendelson B, Wong CH. Changes in the facial skeleton with aging: implications and clinical applications in facial rejuvenation. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2012 Aug;36(4):753-60.

[35] Ali MJ, Ende K, Maas CS. Perioral rejuvenation and lip augmentation. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2007 Nov;15(4):491-500.

[36] de Maio M, Wu WTL, Goodman GJ, Monheit G; Alliance for the Future of Aesthetics Consensus Committee. Facial Assessment and Injection Guide for Botulinum Toxin and Injectable Hyaluronic Acid Fillers: Focus on the Lower Face. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017 Sep;140(3):393e-404e.

[37] Rohrich RJ, Pessa JE. The anatomy and clinical impli- cations of perioral submuscular fat. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124:266–271.

[38] Ali MJ, Ende K, Maas CS. Perioral rejuvenation and lip augmentation. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2007 Nov;15(4):491-500.

[39] Ramaut L, Tonnard P, Verpaele A, Verstraete K, Blondeel P. Aging of the Upper Lip: Part I: A Retrospective Analysis of Metric Changes in Soft Tissue on Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019 Feb;143(2):440-446.

[40] Ali MJ, Ende K, Maas CS. Perioral rejuvenation and lip augmentation. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2007 Nov;15(4):491-500.

[41] Hodgkinson DJ. Identifying the body-dysmorphic patient in aesthetic surgery. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2005 Nov-Dec;29(6):503-9.

[42] Wang Q, Cao C, Guo R, Li X, Lu L, Wang W, Li S. Avoiding Psychological Pitfalls in Aesthetic Medical Procedures. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2016 Dec;40(6):954-961.

[43] DeJoseph LM, Agarwal A, Greco TM. Lip Augmentation. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2018 May;26(2):193-203.

[44] de Maio M, Wu WTL, Goodman GJ, Monheit G; Alliance for the Future of Aesthetics Consensus Committee. Facial Assessment and Injection Guide for Botulinum Toxin and Injectable Hyaluronic Acid Fillers: Focus on the Lower Face. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017 Sep;140(3):393e-404e.

[45] Ramaut L, Tonnard P, Verpaele A, Verstraete K, Blondeel P. Aging of the Upper Lip: Part I: A Retrospective Analysis of Metric Changes in Soft Tissue on Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019 Feb;143(2):440-446

[46] DeJoseph LM, Agarwal A, Greco TM. Lip Augmentation. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2018 May;26(2):193-203.

[47] DeLorenzi C. Complications of injectable fillers. Aesthet Surg J. 2013;33:561–575.

[48] Richey PM, Norton SA. John Tyndall’s Effect on Dermatology. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153(3):308.

[49] Mannino GN, Lipner SR. Current concepts in lip augmentation. Cutis. 2016;98: 325–9.

[50] Fulton J, Caperton C, Weinkle S, Dewandre L. Filler injections with the blunt-tip microcannula. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012 Sep;11(9):1098-103.

[51] Blandford AD, Hwang CJ, Young J, Barnes AC, Plesec TP, Perry JD. Microanatomical Location of Hyaluronic Acid Gel Following Injection of the Upper Lip Vermilion Border: Comparison of Needle and Microcannula Injection Technique. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2018 May/Jun;34(3):296-299.

[52] Tansatit T, Apinuntrum P, Phetudom T. A Dark Side of the Cannula Injections: How Arterial Wall Perforations and Emboli Occur. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2017 Feb;41(1):221-227.

[53] Surek CC, Guisantes E, Schnarr K, Jelks G, Beut J. “No-Touch” Technique for Lip Enhancement. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016 Oct;138(4):603e-613e.

[54] de Maio M, Wu WTL, Goodman GJ, Monheit G; Alliance for the Future of Aesthetics Consensus Committee. Facial Assessment and Injection Guide for Botulinum Toxin and Injectable Hyaluronic Acid Fillers: Focus on the Lower Face. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017 Sep;140(3):393e-404e.

[55] Cengiz AF, Goymen M, Akcali C. Efficacy of botulinum toxin for treating a gummy smile. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2020 Jul;158(1):50-58.

[56] Mazzuco R, Hexsel D. Gummy smile and botulinum toxin: a new approach based on the gingival exposure area. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010 Dec;63(6):1042-51

[57] de Maio M, Rzany B. Botulinum Toxin in Aesthetic Medicine. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer-Verlag; 2009

[58] de Maio M, Wu WTL, Goodman GJ, Monheit G; Alliance for the Future of Aesthetics Consensus Committee. Facial Assessment and Injection Guide for Botulinum Toxin and Injectable Hyaluronic Acid Fillers: Focus on the Lower Face. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017 Sep;140(3):393e-404e.

[59] Lowe NJ, Yamauchi P. Cosmetic uses of botulinum toxins for lower aspects of the face and neck. Clin Dermatol. 2004;22(1):18-22.

[60] de Maio M, Rzany B. Botulinum Toxin in Aesthetic Medicine. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer-Verlag; 2009.

[61] Wu DC, Fabi SG, Goldman MP (2015) Neurotoxins: current concepts in cosmetic use on the face and neck-lower face. Plast Reconstr Surg 136(5 Suppl):76S–79S

[62] Lowe NJ, Yamauchi P. Cosmetic uses of botulinum toxins for lower aspects of the face and neck. Clin Dermatol. 2004;22(1):18-22

[63] de Maio M, Wu WTL, Goodman GJ, Monheit G; Alliance for the Future of Aesthetics Consensus Committee. Facial Assessment and Injection Guide for Botulinum Toxin and Injectable Hyaluronic Acid Fillers: Focus on the Lower Face. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017 Sep;140(3):393e-404e

[64] Carruthers A, Carruthers J, Monheit GD, Davis PG, Tardie G. Multicenter, randomized, parallel-group study of the safety and effectiveness of onabotulinumtoxinA and hyaluronic acid dermal fillers (24-mg/ml smooth, cohesive gel) alone and in combination for lower facial rejuvenation. Dermatol Surg. 2010 Dec;36 Suppl 4:2121-34.

[65] Teixeira JC, Ostrom JY, Hohman MH, Nuara MJ. Botulinum Toxin Type-A for Lip Augmentation: “Lip Flip” [published online ahead of print, 2020 Nov 9]. J Craniofac Surg. 2020;10.1097/SCS.0000000000007128.

[66]Choi YJ, Kim JS, Gil YC, et al. Anatomical considerations regarding the location and boundary of the depressor anguli oris muscle with reference to botulinum toxin injection. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;134(5):917-921.

[67] de Maio M, Wu WTL, Goodman GJ, Monheit G; Alliance for the Future of Aesthetics Consensus Committee. Facial Assessment and Injection Guide for Botulinum Toxin and Injectable Hyaluronic Acid Fillers: Focus on the Lower Face. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017 Sep;140(3):393e-404e

[68] Choi YJ, We YJ, Lee HJ, et al. Three-Dimensional Evaluation of the Depressor Anguli Oris and Depressor Labii Inferioris for Botulinum Toxin Injections [published online ahead of print, 2020 Mar 31]. Aesthet Surg J. 2020

[69] Galadari H, Krompouzos G, Kassir M, Gupta M, Wollina U, Katsambas A, Lotti T, Jafferany M, Navarini AA, Vasconcelos Berg R, Grabbe S, Goldust M. Complication of Soft Tissue Fillers: Prevention and Management Review. J Drugs Dermatol. 2020 Sep 1;19(9):829-832.

[70] Bar-Meir E, Zaslansky R, Regev E, Keidan I, Orenstein A, Winkler E. Nitrous oxide administered by the plastic surgeon for repair of facial lacerations in children in the emergency room. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006 Apr 15;117(5):1571-5.

[71] Smith KC, Comite SL, Balasubramanian S, Carver A, Liu JF. Vibration anesthesia: a noninvasive method of reducing discomfort prior to dermatologic procedures. Dermatol Online J. 2004 Oct 15;10(2):1.

[72] Galadari H, Krompouzos G, Kassir M, Gupta M, Wollina U, Katsambas A, Lotti T, Jafferany M, Navarini AA, Vasconcelos Berg R, Grabbe S, Goldust M. Complication of Soft Tissue Fillers: Prevention and Management Review. J Drugs Dermatol. 2020 Sep 1;19(9):829-832.

[73] Doerfler L, Hanke CW. Arterial Occlusion and Necrosis Following Hyaluronic Acid Injection and a Review of the Literature. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019 Jun 1;18(6):587.

[74] Gupta A, Miller PJ. Management of Lip Complications. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2019 Nov;27(4):565-570.

[75] Fitzgerald R, Bertucci V, Sykes JM, Duplechain JK. Adverse Reactions to Injectable Fillers. Facial Plast Surg. 2016 Oct;32(5):532-55.

[76] Urdiales-Gálvez F, Delgado NE, Figueiredo V, Lajo-Plaza JV, Mira M, Moreno A, Ortíz-Martí F, Del Rio-Reyes R, Romero-Álvarez N, Del Cueto SR, Segurado MA, Rebenaque CV. Treatment of Soft Tissue Filler Complications: Expert Consensus Recommendations. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2018 Apr;42(2):498-510.

[77] Jeong GJ, Kwon HJ, Park KY, Kim BJ. Pulsed-dye laser as a novel therapeutic approach for post-filler bruises. Dermatol Ther. 2018 Nov;31(6):e12721.

[78] Fitzgerald R, Bertucci V, Sykes JM, Duplechain JK. Adverse Reactions to Injectable Fillers. Facial Plast Surg. 2016 Oct;32(5):532-55.

[79] Urdiales-Gálvez F, Delgado NE, Figueiredo V, Lajo-Plaza JV, Mira M, Moreno A, Ortíz-Martí F, Del Rio-Reyes R, Romero-Álvarez N, Del Cueto SR, Segurado MA, Rebenaque CV. Treatment of Soft Tissue Filler Complications: Expert Consensus Recommendations. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2018 Apr;42(2):498-510.

[80] Leonhardt JM, Lawrence N, Narins RS. Angioedema acute hypersensitivity reaction to injectable hyaluronic acid. Dermatol Surg. 2005 May;31(5):577-9.

[81] Kaplan AP, Greaves MW. Angioedema. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005 Sep;53(3):373-88; quiz 389-92.

[82] Fitzgerald R, Bertucci V, Sykes JM, Duplechain JK. Adverse Reactions to Injectable Fillers. Facial Plast Surg. 2016 Oct;32(5):532-55.

[83] Urdiales-Gálvez F, Delgado NE, Figueiredo V, Lajo-Plaza JV, Mira M, Moreno A, Ortíz-Martí F, Del Rio-Reyes R, Romero-Álvarez N, Del Cueto SR, Segurado MA, Rebenaque CV. Treatment of Soft Tissue Filler Complications: Expert Consensus Recommendations. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2018 Apr;42(2):498-510.

[84] Funt D, Pavicic T. Dermal fillers in aesthetics: an overview of adverse events and treatment approaches. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2013 Dec 12;6:295-316.

[85] Fitzgerald R, Bertucci V, Sykes JM, Duplechain JK. Adverse Reactions to Injectable Fillers. Facial Plast Surg. 2016 Oct;32(5):532-55.

[86] Gupta A, Miller PJ. Management of Lip Complications. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2019 Nov;27(4):565-570.

[87] Galadari H, Krompouzos G, Kassir M, Gupta M, Wollina U, Katsambas A, Lotti T, Jafferany M, Navarini AA, Vasconcelos Berg R, Grabbe S, Goldust M. Complication of Soft Tissue Fillers: Prevention and Management Review. J Drugs Dermatol. 2020 Sep 1;19(9):829-832.

[88]Lemperle G, Rullan PP, Gauthier-Hazan N. Avoiding and treating dermal filler complications. Plast Reconstr Surg 2006;118(3, Suppl):92S–107S

[89]Nicolau PJ. Long-lasting and permanent fillers: biomaterial influence over host tissue response. Plast Reconstr Surg 2007;119: 2271–86.

[90] Ibrahim O, Overman J, Arndt KA, Dover JS. Filler Nodules: Inflammatory or Infectious? A Review of Biofilms and Their Implications on Clinical Practice. Dermatol Surg. 2018 Jan;44(1):53-60.

[91] Gupta A, Miller PJ. Management of Lip Complications. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2019 Nov;27(4):565-570.

[92] Fitzgerald R, Bertucci V, Sykes JM, Duplechain JK. Adverse Reactions to Injectable Fillers. Facial Plast Surg. 2016 Oct;32(5):532-55.

[93] Gupta A, Miller PJ. Management of Lip Complications. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2019 Nov;27(4):565-570.

[94] Fitzgerald R, Bertucci V, Sykes JM, Duplechain JK. Adverse Reactions to Injectable Fillers. Facial Plast Surg. 2016 Oct;32(5):532-55.

[95] Galadari H, Krompouzos G, Kassir M, Gupta M, Wollina U, Katsambas A, Lotti T, Jafferany M, Navarini AA, Vasconcelos Berg R, Grabbe S, Goldust M. Complication of Soft Tissue Fillers: Prevention and Management Review. J Drugs Dermatol. 2020 Sep 1;19(9):829-832.

[96] Ibrahim O, Overman J, Arndt KA, Dover JS. Filler Nodules: Inflammatory or Infectious? A Review of Biofilms and Their Implications on Clinical Practice. Dermatol Surg. 2018 Jan;44(1):53-60.

[97] Rzany B, DeLorenzi C. Understanding, Avoiding, and Managing Severe Filler Complications. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015 Nov;136(5 Suppl):196S-203S.

[98] Fitzgerald R, Bertucci V, Sykes JM, Duplechain JK. Adverse Reactions to Injectable Fillers. Facial Plast Surg. 2016 Oct;32(5):532-55.

[99] Schnabel D, Esposito DH, Gaines J, et al; RGM Outbreak Investiga- tion Team. Multistate US outbreak of rapidly growing mycobacte- rial infections associated with medical tourism to the Dominican Republic, 2013-2014. Emerg Infect Dis 2016;22(8):1340–1347

[100] Gupta A, Miller PJ. Management of Lip Complications. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2019 Nov;27(4):565-570

[101] Ibrahim O, Overman J, Arndt KA, Dover JS. Filler Nodules: Inflammatory or Infectious? A Review of Biofilms and Their Implications on Clinical Practice. Dermatol Surg. 2018 Jan;44(1):53-60.

[102] Fitzgerald R, Bertucci V, Sykes JM, Duplechain JK. Adverse Reactions to Injectable Fillers. Facial Plast Surg. 2016 Oct;32(5):532-55.

[103] Signorini M, Liew S, Sundaram H, et al; Global Aesthetics Consensus Group. Global Aesthetics Consensus: avoidance and management of complications from hyaluronic acid fillers evidence and opinion-based review and consensus recommendations. Plast Reconstr Surg 2016;137(6):961e–971e

[104] Funt D, Pavicic T. Dermal fillers in aesthetics: an overview of adverse events and treatment approaches. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2013 Dec 12;6:295-316.

[105] Urdiales-Gálvez F, Delgado NE, Figueiredo V, Lajo-Plaza JV, Mira M, Moreno A, Ortíz-Martí F, Del Rio-Reyes R, Romero-Álvarez N, Del Cueto SR, Segurado MA, Rebenaque CV. Treatment of Soft Tissue Filler Complications: Expert Consensus Recommendations. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2018 Apr;42(2):498-510.

[106] Jordan DR, Stoica B. Filler migration: a number of mechanisms to consider. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 2015;31(4):257–62.

[107] Woodward J, Khan T, Martin J. Facial Filler Complications. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2015 Nov;23(4):447-58.

[108] King M, Convery C, Davies E. This month’s guideline: The Use of Hyaluronidase in Aesthetic Practice (v2.4). J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2018 Jun;11(6):E61-E68. Epub 2018 Jun 1.

[109] Beleznay K, Carruthers JD, Humphrey S, Jones D. Avoiding and Treating Blindness From Fillers: A Review of the World Literature. Dermatol Surg. 2015 Oct;41(10):1097-117.

[110] Trévidic P, Criollo-Lamilla G. French Kiss Technique: An Anatomical Study and Description of a New Method for Safe Lip Eversion. Dermatol Surg. 2020 Nov;46(11):1410-1417.

[111] van Loghem JAJ, Humzah D, Kerscher M. Cannula Versus Sharp Needle for Placement of Soft Tissue Fillers: An Observational Cadaver Study. Aesthet Surg J. 2017 Dec 13;38(1):73-88.

[112] Rzany B, DeLorenzi C. Understanding, Avoiding, and Managing Severe Filler Complications. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015 Nov;136(5 Suppl):196S-203S.

[113] Fitzgerald R, Bertucci V, Sykes JM, Duplechain JK. Adverse Reactions to Injectable Fillers. Facial Plast Surg. 2016 Oct;32(5):532-55.

[114] Woodward J, Khan T, Martin J. Facial Filler Complications. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2015 Nov;23(4):447-58.

[115] Fitzgerald R, Bertucci V, Sykes JM, Duplechain JK. Adverse Reactions to Injectable Fillers. Facial Plast Surg. 2016 Oct;32(5):532-55.

[116] Galadari H, Krompouzos G, Kassir M, Gupta M, Wollina U, Katsambas A, Lotti T, Jafferany M, Navarini AA, Vasconcelos Berg R, Grabbe S, Goldust M. Complication of Soft Tissue Fillers: Prevention and Management Review. J Drugs Dermatol. 2020 Sep 1;19(9):829-832.

[117] Cohen JL, Biesman BS, Dayan SH, et al. Treatment of hyaluronic acid filler-induced impending necrosis with hyaluronidase: consensus recommendations. Aesthet Surg J 2015;35(7):844–849

[118] Hwang CJ, Morgan PV, Pimentel A, Sayre JW, Goldberg RA, Duckwiler G. Rethinking the role of nitroglycerin ointment in ischemic vascular filler complications: an animal model with ICG imaging. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 2016;32(2):118–122.

[119] Cohen JL, Biesman BS, Dayan SH, et al. Treatment of hyaluronic acid filler-induced impending necrosis with hyaluronidase: consensus recommendations. Aesthet Surg J 2015;35(7):844–849