Statement of Funding Support

None

Financial Disclosures

- Galderma: clinical investigator, speaker, consultant, advisory board member

- Merz: clinical investigator, speaker, advisory board member

- BTL: clinical investigator, speaker, consultant, advisory board member

ABSTRACT

Nonsurgical options for gluteal enhancement are gaining popularity as a no to minimal downtime alternative to surgical approaches. A proper understanding of gluteal anatomy and a systemic approach to evaluating the gluteal region is required for safe and restorative buttock enhancement. Current FDA-approved devices, injectable- or energy-based, offer treatment to the skin, fat, and muscle of the gluteal region. An appreciation of each device’s advantages, disadvantages, best practices, adverse events, and outcomes is necessary to deliver pleasing results in nonsurgical gluteal enhancement. Nonsurgical buttock enhancement is rising in popularity and can be combined with other body contouring procedures to provide more comprehensive, full-body approaches with cosmetic procedures.

Introduction

Gluteal rejuvenation has been an area of surgical focus since 1969, when the first case report of unilateral buttock augmentation was documented by Bartels et al.1 Over the past five decades, surgical approaches including liposuction, fat transfer, and gluteal implants have been researched, performed, improved, and reported.2 Buttock augmentation is a rising star among cosmetic procedures. According to ASAPS 2016 data, 20,000 buttock augmentation were performed in the U.S., an over 3267% increase from 2002.3 Similarly, the 2016 International Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgery reported similarly impressive numbers of buttock rejuvenation procedures worldwide with 31,330 augmentation procedures with gluteal implants and 300,791 fat transfer procedures globally.4

The popularity of gluteal enhancement has been propelled by pop culture and celebrity appearance. Remember song lyrics to “Baby Got Back?” Or the Instafamous celebrities with dramatically enhanced waist-to-hip ratios over time? Celebrity influence has created consumer-driven behavior that has led to trends in aesthetics and health care.5 Google Trends data clearly shows a temporal relationship between celebrity news and public interest in procedures from prophylactic BRCA-related mastectomies to buttock enhancement.6 Curiosity becomes sustained public awareness and increased consumer interest in cosmetic surgery over time.

With rising popularity and increasing numbers of gluteal enhancement surgery came a steady increase in rare but devastating complications from gluteal autologous fat transfer. ASAPS, through the Aesthetic Surgery Education and Research Foundation, assembled a Gluteal Fat Grafting Task Force to evaluate 25 deaths occurring in the U.S. and 22 in Mexico and Colombia.3 Fat embolism from vascular penetration during gluteal fat transfer is an unfortunate but possible adverse event from surgical procedures intended for buttock beautification. The risk of death from autologous fat transfer to the gluteal region is estimated at 1:3000.7 The risk of surgery in the gluteal region has propelled the search for safer, noninvasive/nonsurgical alternatives with little to no downtime.

Nonsurgical injectable and energy-based devices offer in-office treatment to enhance the gluteal region. These targeted therapies can be used to target three tissue planes within the gluteal region: muscle, fat, and skin. Nonsurgical gluteal enhancement offers the potential advantages of little to no downtime, gradual but meaningful results, and safer alternatives to fat grafting. However, nonsurgical gluteal enhancement is not without its potential drawbacks. The amount of material needed for significant rejuvenation may be cost prohibitive, and results are in most cases not permanent, requiring some level of maintenance therapy. Patient desires, medical history, and lifestyle must all be balanced and discussed when weighing surgical versus nonsurgical options for buttock enhancement.

Anatomy & Classification of the Gluteal Region

In order to perform rejuvenating procedures safely on the buttocks, thorough anatomic familiarity is of paramount importance. In this section, both the anatomy of the gluteal region as well as classification systems of the buttocks region are reviewed.

Anatomical Framework of the Buttocks Region

There are seven distinct tissue layers to consider when evaluating the buttock region. This chapter will cover treatment options to enhance only a minority of them, namely fat, muscle, and to some extent, skin. In order from superficial to deep planes, the distinct layers of the buttock region include the skin, superficial fat, superficial fascia, deep fat, deep fascia, muscle, and bone.8 It is important to note that these layers hold true regardless of gender or laterality (left versus right side).

According to Mendieta,3 four anatomic variables determine overall buttock shape, three of which we can now manipulate surgically or nonsurgically through cosmetic procedures. The first variable is the underlying bony framework of the pelvis. This is a fixed structure unless altered by orthopedic surgery, trauma, joint disease or osteoporosis. The size, width, and height of the pelvic bones influences shape but is not altered by cosmetic surgery.

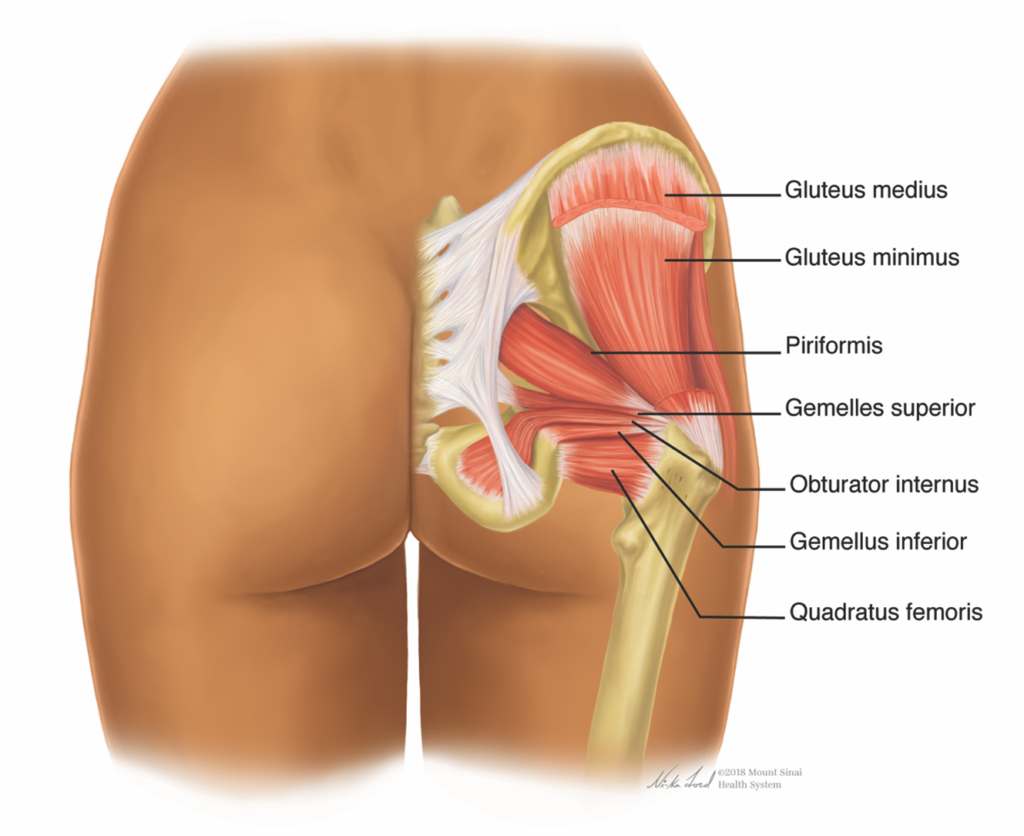

The second anatomic structure contributing to overall shape of the buttocks region is muscle. Important to gluteal implants, this plane is useful for prostheses but avoided during autologous fat transplantation. Recently, nonsurgical options targeting muscle hyperplasia and hypertrophy have emerged.9 There are two major muscle groups, a superficial and deep, that contribute to the gluteal region’s appearance.10 The superificial muscles, for which the region is commonly named, include the gluteus maximus, medius and minimus (FIGURE 1).

Along with the gluteal muscle complex, the laterally-oriented tensor fascieae latae round out the superficial muscles of the buttocks region. Smaller muscles comprise the deep muscle group. These include the piriformis, obturator internus, quadratus femoris, superior & inferior gemellus (FIGURE 2).10

Fat is the third anatomic structure contributing to shape of the buttocks region. It can be greatly manipulated and easily accessed to change buttock shape. Several regions of fat deposition from waist to thigh influence gluteal aesthetics. The supragluteal, paralumbar, trochanteric and subgluteal regions comprise the most important network of fat related to gluteal shape. Age, weight changes, trauma, or other physiologic/metabolic disorders can cause imbalance within these regions, most often resulting in a “squaring” of the buttocks region. Subtractive and additive strategies such as liposuction in some regions and complementary autologous fat transfer in others were the traditional means of re-shaping the buttocks.11

The skin, the superficial most layer of the buttocks region, is the final anatomical variable influencing gluteal shape.3,12 The integument suffers from atrophy, ptosis, and laxity over time. More aggressive maneuvers for skin rejuvenation include skin excision or a buttock lift for improvement. Nonsurgical rejuvenation through injectable and laser or energy-based devices may provide nonsurgical options for skin rejuvenation to the gluteal region.

Gluteal Frame Shapes

In 2006, Mendieta published four basic shapes relating to the buttocks region.3 Termed “Gluteal Frame Shapes,” it provides a clear classification system for the physician when evaluating and treating the buttocks region. The most commonly occurring gluteal frame shape is the square, occurring approximately 40% of the time. It is successfully addressed with fat subtractive procedures such as liposuction or noninvasive fat reduction. The second most commonly encountered buttock shape is the A-shape or “pear” shape, occurring in about 30% of cosmetic patients. In this frame shape, the fat is concentrated more readily in the inferior region of the upper lateral thigh, and less so in the hip region, leading to a bottom heavy appearance. Treatment strategies in this case address fat removal inferiorly, with volume augmentation to the superior regions of the buttocks. The third most common gluteal shape is the round, occurring about 15% of the time. These patients tend to have higher BMI with excess fat distribution above the greater trochanter. The final gluteal frame shape occurring roughly 15% of the time is the V-shape or “apple” shape. These patients tend to have central obesity, thin legs, and a tall pelvis. Apple-shaped gluteal regions are the most challenging to enhance, often requiring larger volumes in the inferior and lateral regions of the buttocks.13

Vascular Supply

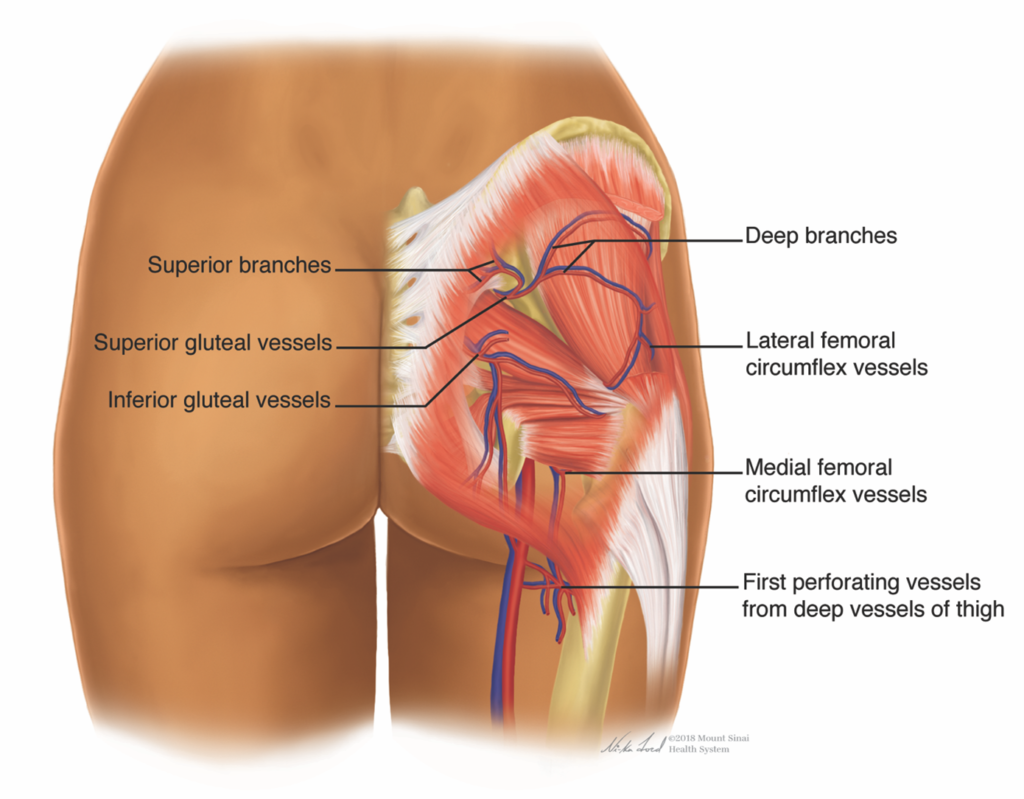

The vasculature of the gluteal region must be well-understand in order to minimize the risk of serious adverse events during surgical or injectable procedures (FIGURE 3).

Embolic events from fat transfer, with rare fatal outcomes, have highlighted the need for safety and anatomical familiarity when approaching buttock augmentation.14

A triangle of danger exists in procedures performed within the boundaries from the posterior superior iliac spine superiorly to the greater trochanter laterally, and the ischial tuberosity inferiorly.15 It is hypothesized that fat embolic and thromboembolic phenomenon following injections exist when gluteal veins are transected, allowing fat macro- or microparticles to be injected intravascularly. The superior and inferior gluteal veins around the piriformis muscle are the hypothesized and vulnerable region of gluteal vasculature prone to transection during injectable procedures.13,16

Lin et al. provided an excellent review of the gluteal vascular anatomy.10 On the arterial side, the gluteal region is served by terminal branches from the internal iliac artery, the superior and inferior gluteal arteries. The superficial buttock muscles – gluteus maximus, medius, and minimus muscles – are supplied by the superior gluteal artery. Alternately, the inferior gluteal artery traverses the greater sciatic foramen to supply the sciatic nerve and deep muscles of the pelvic floor, hip and posterior thigh.

On the venous side, the gluteal veins are part of a regional network of veins that carry blood from the pelvic region back to the superior vena cava. The superior and inferior gluteal veins are paired with their correspondingly named arteries and are most vulnerable to vasculo-occlusive and embolic events during cosmetic surgery.10 The gluteal veins travel over the piriformis muscle, enter through the greater sciatic foramen, and join as a single vein to terminate into the internal iliac vein.

Surgical Buttock Augmentation and Possible Complications

The first attempts at surgical gluteal implants were reported in the late 1960s and early 1970s. In the first report by Bartels, unilateral gluteal muscle atrophy was corrected with a surgical silicone breast implant adapted for buttock region use.17,18 In 1973, Cooke and Ricketson used Dacron patches with implants to minimize implant migration and improve the lateral gluteal depression or hip dell.17,18 For the past 50 years, surgical techniques in gluteal restoration and enhancements have been refined. Typically, surgical approaches to gluteal enhancement involve liposuction with autologous fat transplantation, gluteal implants, or a combination approach. According to 2016 ASAPS data, gluteal enhancement procedures consisted of 8% gluteal implants and 92% autologous fat transfer.16

There are substantial risks associated with both surgical methods of gluteal enhancement. Herein lies a brief discussion of current methods and risks associated with both gluteal implants and autologous fat transfer. It is important to understand the established risks of surgical procedures when becoming familiar with nonsurgical options for buttock augmentation.

Gluteal implants consist of semisolid silicone elastomer and are described by three surgical approaches of placement: subcutaneous, subfascial or intramuscular, and submuscular.16 The intramuscular plane is the favored area of placement. Superficial placement in the subcutaneous plane has an unsatisfactory cosmetic appearance, leading to palpability and visible margin, implant migration, ptosis, extrusion and even encapsulation.17

Placement of intramuscular gluteal implants is bloody and often a painful, 1-2 week recovery for patients.17 There is an 8.8% overall complication with this surgical approach.16 In early reports, wound dehiscence and challenges with tissue coverage tight closure occurred in as high as 80% of cases;17 current data points to as much as 30-40% of cases.16 Sciatic paresthesias occurred as often as 20% of the time in early reports),17 but the incidence has now decreased. Seromas, infection, asymmetry, implant migration or malposition, implant rupture, and capsular contracture occur with incidences between 1 to 5%.16,17 Large implant surgeries (greater than 350 cc) and overweight patients are more likely to experience loss or exposure of a gluteal implant.17

Autologous fat transfer can provide dramatic and lasting changes to the gluteal region, but also carry a known and devastating risk of fat embolism. The first reports of fat transfer involved a little over 200 cc of fat to each buttock; current procedures often necessitate 500-900 cc per buttocks.17 The risk of fat emboli through cannula disturbance and implantation into the gluteal veins is real. So much a concern were the rare but dire consequences of autologous fat transfer to the buttocks, that the ASAPS Aesthetic Surgery Education and Research Foundation formed a gluteal fat grafting task force to investigate risks associated with this procedure.3 Twenty-five U.S. deaths and another 22 in Mexico and Colombia were evaluated. It was found that although there was no correlation between volume of fat transplanted and fat embolization events, deep gluteal maximus placement of fat should be avoided. It is advised that larger cannulas be used and the target placement planes should be the subcutaneous compartment to superficial muscular layer.3

The overall complication rate following autologous fat transfer to the gluteal region is approximately 7% 17,19, although individual papers have widely varying rates of individual adverse events. Interviewing of 4843 plastic surgeons by the Aesthetic Surgery Education and Research Foundation Task Force found 3% of surgeons had a fatality, and 7% had at least 1 pulmonary fat embolism event following gluteal fat transfer.7 The risk of death associated with this procedure is estimated as 1:3000.7 Other associated risks with autologous fat transfer to the buttocks include the following: seroma (3.5%-10%), cellulitis (0.3-18%), infection (14%), tissue irregularities (12%), symptomatic hypovolemia, sciatic nerve injury, fat necrosis and oil cysts, partial resorption of fat, disseminated intravascular coagulation (<1%), and pulmonary embolism (<1%).14,16 It should also be noted that obese patients with a BMI of greater than 30 kg/cm2 experience higher complication rates following aesthetic and massive weight loss body contouring.13

Aging & Physiological Changes Related to the Buttock Region

Age-Related Changes in the Gluteal Region

The march of time has predictable and recognized changes in the gluteal region. The skin envelope, adipose layer, and muscle undergo atrophy and diminution with advancing age. The cumulative effect of decreased fat and muscle tone leads to buttock ptosis, increase in the buttock height, lengthening of both the infragluteal fold and intergluteal crease, and accentuation of skin laxity and cellulite in the gluteal region.13,20,21

Platypygia is the medical term which describes flattening of the buttocks.22 Buttock ptosis, or sagging, is defined by Gonzalez as the “prolapse or slipping out of place of an organ. In the gluteal region, this is observed as redundant buttocks tissue that inferiorly crosses the infragluteal fold at the midline of the posterior thigh.”23 Ptosis is graded on a four-point scale from 0-III depending on the degree of skin drooping below the infragluteal fold when observed on lateral view. Zero is defined as no redundancy, while III is extreme skin drooping well below the infragluteal fold.24

Gluteal fat changes over time have been studied. There is a general accumulation of adipose tissue in the abdominal and pelvic region, but loss of adipose volume in the buttock.21 In post-menopausal women, there is also hypertrophy of intra-abdominal fat coupled with diastasis recti, skin laxity, and buttock ptosis.21 An ultrasound study of 150 patients reviewed gluteal anatomical changes by gender, age, and BMI. With increasing age and controlling for BMI, gluteal subcutaneous fat increased with increasing age.8 In men with low BMI, they experienced an increase in the subcutaneous layer thickness greater than women. If BMI remained constant over time, there was an increase in the deep fat layer and a decrease in the superficial fat layer with increasing age.8

Peak muscular performance and muscle mass occurs during the second and third decade of life.25 Sarcopenia, or the age-related changes in muscle mass and strength, can lead to metabolic and functional issues that greatly impact health, mobility, balance, and quality of life.26-28 As a large and powerful muscle group, rehabilitation, and maintenance of the gluteal muscle group likely play a role in overall health. Fortunately, published literature on strength training demonstrates age-related effects on skeletal muscle are largely reversible.29 Newer noninvasive technology discussed in this chapter can provide an increase in muscle mass through muscle hypertrophy and hyperplasia.9,27 Maintenance of muscle mass plays a role not only in the aesthetic attributes of the gluteal region but overall health.

Weight-Related Changes in the Gluteal Region

Weight gain can have significant aesthetic implications for the buttocks. Generally speaking, excess weight gain causes ptosis, and increase in buttock height and width, lengthening of the intergluteal crease, and shortening of the infragluteal fold.21 An ultrasound study of 150 individuals with equal gender distribution found distinct changes with increasing BMI.8 An increase in BMI was correlated with an increase in thickness of the subcutaneous compartment, predominately the superficial over deep layer.8

Characteristics of the Ideal Buttocks

With a fundamental understanding of anatomy, categorization, and aging changes of the buttocks, one can now approach beautification of the gluteal region. What composes a beautiful buttocks has provoked discussion and art over the millennia. More recent published discussions have distilled universal tenets and quantitative measurements to guide buttock rejuvenation.18

Basic Principles of Gluteal Beauty

Regardless of ethnic considerations, anthropologic studies have demonstrated consistent adherence to a type of golden ratio in the gluteal region: an approximately 0.7 value for the waist-to-hip ratio.30 This provides the classic “hourglass” silhouette desirable to both female patients and male/female observers. For more conservative patients, 0.70 is the most universally accepted waist-to-hip ratio. Patients desiring greater buttock enhancement may approach a waist-to-hip ratio closer to 0.65.19 The waist-to-hip ratio is generated by a measurement of the narrowest portion of the waist to the buttock measurement at the level of maximal circumference.31

It is important to not consider the buttock in a vacuum, but also consider transitioning body parts around the gluteal region. The buttocks-to-thigh transition has also been evaluated for attractiveness.32 A smooth and gradual transition from buttocks to thighs is considered most attractive as viewed posteriorly. Providing overgenerous volume augmentation to the buttocks with unaugmented thighs creates a “lollipop deformity” aka “marshmallow on a stick” appearance.32 In coronal view, the thigh can be wide and considered quite attractive. On lateral/sagittal view, a thinner thigh is preferred.

Consistent themes of buttock attractiveness arise from the literature. This includes a rounded buttocks with maximal projection at the level of the pubic symphysis, equating to the upper and mid buttocks region.17,23 There should be a smooth and inward sweep to the lumbosacral area and waist on lateral view, as well as no infragluteal crease or buttock ptosis.17 Similar to faces, asymmetry commonly exists in the gluteal region.24 It is important to identify these and discuss with the patient prior to executing a treatment plan.

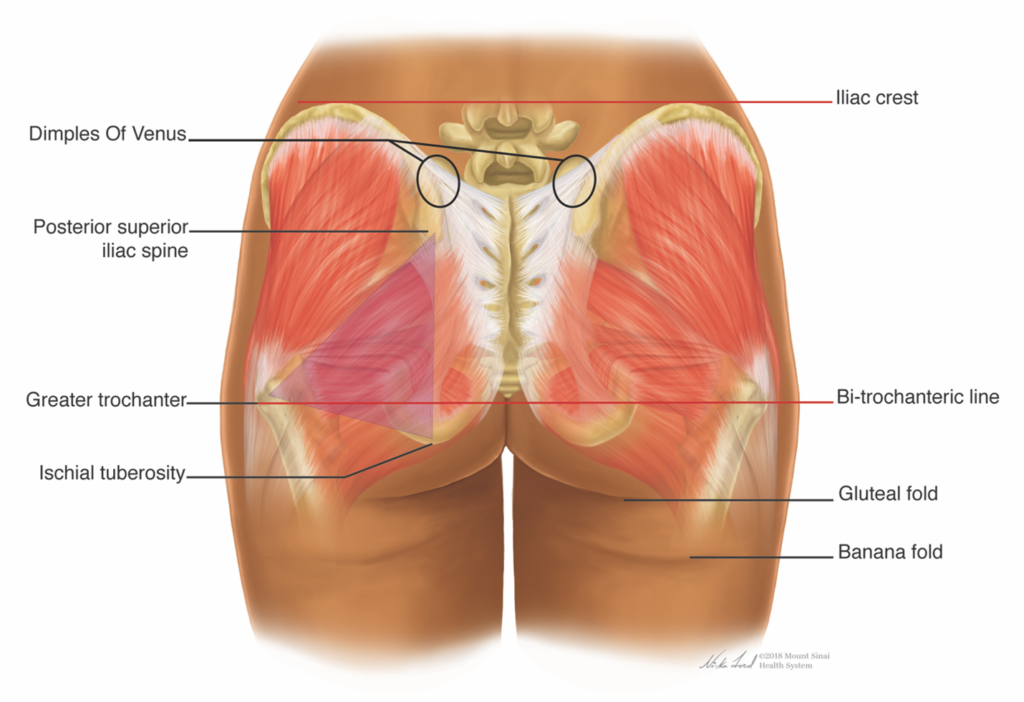

Evaluation of Buttocks on Posterior View

Four anatomical landmarks on posterior view are helpful when guiding enhancement of the gluteal region. This includes the following: lateral hip depression, infragluteal cleft, supragluteal fossettes (or sacral dimples), and the sacral triangle.21,23 Each feature is discussed separately FIGURE 4).

The lateral hip depression, or trochanteric depression, is created by the insertional confluence of the buttock and thigh muscles. In an athletically toned buttock, it is highlighted and prominent. It is, however, important to note that some personal and ethnic variations exist. Some patients, historically Black or Hispanic, have preferred to de-emphasize or even exaggerate and fill the lateral trochanteric depressions.21

The infragluteal cleft delineates the inferior border of the buttocks. It consists of thick fascial insertions originating from the femur and pelvic bones and terminating through intermuscular fascia to the skin. The ideal infragluteal cleft is none at all, but instead a smooth transition from buttocks to thigh.24 The ideal direction of the infragluteal fold from medial to lateral is downward sloping. Furthermore, a diamond-shaped space should be formed between the gently sloping infragluteal fold and the inner thigh.3 An aged buttock region is marked by changes in the infragluteal fold. It descends due to ptosis, elongates laterally, and becomes horizontal to upward sloping.21,24

Sacral dimples are twin depressions located laterally to either side of the medial sacral crest.11 These supragluteal fossettes are considered attractive but not universally present.

The final feature on posterior view considered attractive in buttock enhancement is upper gluteal cleavage. This is formed by a V-shaped attachment zone in the sacral triangle. The triangle is formed from the two depressions of the posterior superior iliac spines (PSIS) to the coccyx inferiorly.21

Evaluation of Buttocks on Lateral View

Projection of the buttocks is the most important feature of attractiveness on lateral view.21 A horizontal line drawn from the level of the pubic symphysis indicates the area of maximal gluteal projection.3,33 The gluteal region on profile should form a C-like shape. There are three zones of the lateral buttock view: upper, central and lower.3 In some patients, spinal hyperextension manifesting as five to seven degrees of lumbar hyperlordosis is considered attractive.21

A Systematic Approach to Gluteal Evaluation

Putting it all together, it is helpful to have a systemic framework when assessing the buttocks and developing a proper treatment plan.13 The following represents a helpful and stepwise approach to assessing the gluteal region:

- Bony framework: assess the pelvis. Is it tall, average, or short in height.

- Gluteal frame shape: square, A-shape (pear), round, or V-shape (apple).

- Lateral trochanteric depression: presence or absence, what are patient preferences?

- Sacral height to intergluteal crease length: ideal ration should be less than or equal to one-third.

- Gluteal muscles: Is shape tall, intermediate or short? Evaluate inferior base width and volume distribution in all quadrants of gluteal region.

- Four junction points on posterior view: Assess V-zone of supragluteal cleavage, diamond space of infragluteal cleft to inner thigh, slope of infragluteal fold, and lateral buttock to thigh transition. All should be smooth transitions.

- Ptosis: Evaluate skin droop over gluteal fold on lateral view. Grade 0-III.

Possible Ethnic Considerations

Several articles in the gluteal implant and fat transfer literature have identified generalizations in ideal buttocks by ethnic group.21,34 These are broad generalizations, and do not hold true for every individual amongst a particular ethnic heritage. It is important to consider patient desires and goals as well as basic tenets of gluteal beauty before generalized guidelines in some ethnic groups. Common findings amongst experience surgeons in gluteal enhancement are discussed below.

Black patients may desire a fuller buttocks full upper and lateral buttocks without a lateral depression. The trochanteric area is prominent and filled. The lateral thigh is generous and is considered a sign of fertility. The “hip” is defined by many patients as the lateral trochanteric area rather than the iliac crest. Hispanic patients show a similar preference profile. A full lateral buttocks and thigh is often requested. A very small waist circumference and very full buttocks are desired by most patients.

Asian patients skew toward a small to medium overall buttocks size. Lateral hip depressions are favored with a lack of lateral thigh fullness. White patients, may have wide variation in requests for gluteal enhancement. Athletic frames may prefer a smaller buttocks, less projection, and lateral buttock depression. Caucasian patients desiring a more classically feminine silhouette commonly request fuller, founded buttocks. Generally speaking, white patients less commonly request added fullness to the lateral thigh region.

Treatment Options

Fat Removal

Subtractive approaches of adjacent areas to the gluteal region can enhance the overall appearance of the buttocks.11 Although beyond the scope of this chapter, surgical and nonsurgical options of fat removal provided needed balance, symmetry, and transition between aesthetic units of the buttocks. Liposuction and noninvasive fat removal through cryolipolysis, radiofrequency, laser, or ultrasound technology are all options that may be explored when discussing gluteal rejuvenation.20 It is important to consider fat removal as a complement to gluteal augmentation, and they may occur in parallel with additive procedures to the buttocks.

Hyaluronic Acid

Background

Hyaluronic acid (HA) fillers have been approved for use in the U.S. since 2003. The majority of indications for these temporary and reversible fillers are for use in the face, though recent indications have included off-face placement such as the hands. Large, volumetric HA filling agents are not available in U.S.20

Macrolane (Q-Med AB, Uppsala, Sweden) became approved for body contouring applications outside the U.S. in 2007. This Restylane family product is a non-animal stabilized hyaluronic acid gel composed of 98% water and 2% HA.35

Treatment

One of the strongest advantages of HA as a buttocks rejuvenation injection device and method is its biological behavior. It is biodegradable with a known reversing agent, hyaluronidase. It is biocompatible and provides meaningful but non-permanent results.

Treatment with HA for buttock rejuvenation is relatively comfortable and time effective 35 The procedure takes about 20 minutes to complete. The skin should be prepared in a sterile manner, and all efforts should be made to ensure placement adheres to a very clean or approximating a sterile complete given a temporary injectable implant is being placed in large quantities. Prophylactic antibiotics are often provided to patients prior to filler placement.36

Most commonly, slit incisions, approximately 5 mm in size, is created after local anesthesia placement in the buttocks. One to several may be placed per buttocks to provide adequate cannula access to anatomical regions of the buttocks requiring volume replenishment. The intended plane of filler placement is the subcutaneous fat,37 Most often, large bore cannulas, 12-16 gauge in size, are used for HA placement. Volume replacement of 40 to 400 mL of HA filler is documented in the literature to accomplish visible restoration of the buttock shape and contour.35,36 Approximately 250-340 mL of HA filler to the buttocks is reported to be effective in published studies. As HA is not packaged as large volumes for aesthetic applications in the U.S., it makes this approach to noninvasive nearly impractical and off-label.

Outcomes

Three published studies have examined the use of NASHA filler for use in buttock augmentation. The largest and longest study was a multicenter, 24-month prospective trial of Macrolane for buttock enhancement 35 Study sites in Belgium, Spain, and Sweden recruited 60 subjects with a mean age of 41. The subject pool was 93% female. Patients were treated with the HA filler using a multiple incision site – cannula technique to the buttocks. The average volume of HA filler placed per subject at initial treatment and optional 8 week touch-up treatment was 340 mL. The procedure was deemed well-tolerated by study subjects with 70% satisfaction at one month follow-up. However, by 24 months following treatment, patient satisfaction decreased dramatically to only 33%.

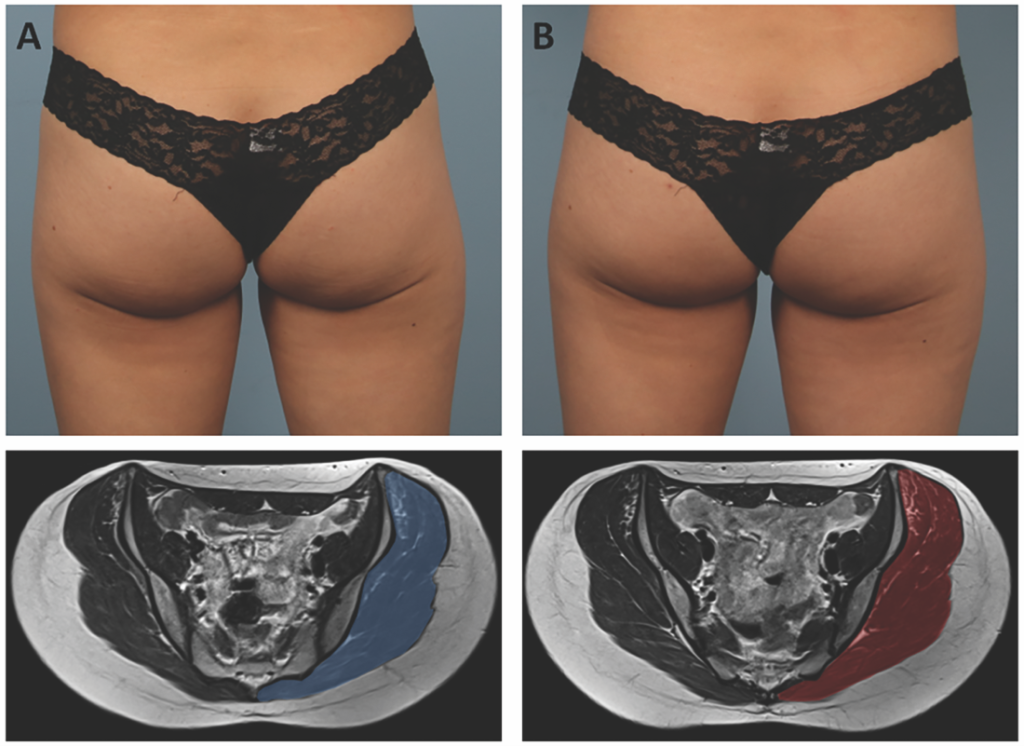

In 2013, Camenisch et al.37 published a smaller study of 8 patients with a mean age of 45 undergoing buttock augmentation with Macrolane. Only one patient in the subject set was male, and patients could receive 40 mL of HA filler per buttocks, up to 400 mL, through a 16 gauge cannula delivery method. MRI imaging was completed following HA filler placement. It demonstrated a globular subcutaneous pattern with feathering pattern inside gluteal muscle. Despite an intended target of subcutaneous fat plane placement, 40% or more of the HA immediately after placement was found in muscle following treatment. At 24 months, 60% of gel was located in the subcutaneous compartment. Summarizing the serial MRI results, HA gel placed intramuscularly tended to degrade more quickly.

A small pilot study for HA filler to the buttocks for the treatment of HIV lipoatrophy was conducted by Claude et al.36 This prospective study of 10 patients recruited study subjects who had severe discomfort of the buttocks region while sitting due to lack of subcutaneous support. Similar to the other studies, up to 400 mL of HA filler could be injected, although the mean volume was 271 mL. Similar to other studies, a cannula technique was used to place the HA product, and all patients received prophylactic antibiotics. At 12 months, only 31% of the HA product was estimated to be remaining.

Adverse Events/Precautions

The majority of adverse events following hyaluronic acid filler placement to the buttock region were mild and temporary. Implant site swelling and soreness are common in the days following treatment. Infection is a reasonable concern and possible risk given the anatomical area of placement. Despite prophylactic antibiotics, two of the three studies experienced infections amongst their study subjects. In the international multicenter study of 60 subjects,35 one infection was considered moderate in severity. In the HIV lipoatrophy study of 10 subjects, 5 patients experienced localized inflammation or effusions in the areas of placement.36

The MRI imaging study37 reveals that although the intended plane of injection was the subcutaneous compartment, nearly half of the HA filler was delivered into the muscle, an area at higher risk for severe complications such as vascular access and filler embolization.

Volumes required for meaningful and effective results make HA filler for buttock rejuvenation cost-prohibitory. HA filler in the U.S. has been supplied as 1 or 2 mL syringes for cosmetic use, making transplantation of 250-350 mL of filler to the buttocks region impractical and extremely expensive. Hyaluronic acid filler is considered temporary, and 2 year follow-up and 1 year MRI imaging shows a dramatic decrease in remaining implantable filler.36,37

PLLA

Background

Poly-L-lactic acid has been approved for over 20 years as a biostimulatory agent for volume correction. First to market in Europe as NewFill in 1999,38 it became known as Sculptra in the U.S. PLLA was first FDA-approved in 2004 for HIV lipoatrophy, but was quickly adopted for off-label use in the immunocompetent population for facial rejuvenation.39 In 2009, it received FDA-approval as Sculptra Aesthetic (Galderma Laboratories, Fort Worth, TX) for the correction of moderate to severe facial folds and wrinkles such as nasolabial folds. Despite the label’s relatively restrictive nature, experienced injectors of PLLA have found sophisticated facial and body applications for this collagen stimulating agent.

PLLA is supplied as a sterile, lyophilized powder that is produced from non-GMO corn and beets. It is stored in a glass vial that does not require sterilization or refrigeration. The shelf life of the product is approximately 24 months from the time of manufacturing. Each vial contains 40.8% (367.5 mg) of poly-L-lactic acid, 34.7% of non-pyrogenic mannitol (osmotic agent), and 24.5% carboxymethylcellulose (emulsifying agent).10,39

PLLA is a synthetic polymer of lactic acid. It is both biodegradable and biocompatible. The particle size is deliberate. At 40-63 µm in size, PLLA particles evade phagocytosis but do not go unnoticed. Instead, PLLA particles elicit a controlled fibroblastic responses that eventuates in new collagen formation. PLLA particles are broken down by nonenzymatic hydrolysis into lactic acid monomers, carbon dioxide, and water.40,41 The subclinical fibroblastic response elicited by PLLA degradation results in type I collagen formation.42 This ultimately results in a volumizing effect on the tissues that can mimic bone or soft tissue loss, as well as an increase in dermal thickness that may have implications on skin quality.38

Treatment

PLLA injection therapy is completed as a series of treatments. The product is reconstituted with sterile water for injection, and may be immediately reconstituted for use.43 Immediate reconstitution and admixing of lidocaine into the PLLA suspension have been studied through a multicenter, prospective, noninferiority trial for facial treatment and are likely to lead to a label change in the future (Dr. Palm, personal communication).

Generally speaking, larger dilution volumes (12-16 mL or more per vial) are typically preferred for off-facial treatment..20 Dilutions of PLLA for gluteal region application increased with the majority of respondents in a 2019 paper.44 According to the survey, many injectors use at least 10-30 mL dilutions per vial for buttock enhancement. Similar to facial applications, PLLA placement in the buttocks is conducted as a series of treatments. Treatment intervals vary, but are commonly 4-8 weeks apart.10

The goals of PLLA administration to the buttock region include tightening, volumizing, and reducing cellulite.40 Treatment of localized lipotrophs following liposuction and stretch marks may also be targeted for improvement in the process of buttocks enhancement with PLLA.42 Skin quality improvements generally are delivered with large dilutions and a smaller number of sessions and treatment vials for meaningful results. True volume correction often requires large numbers of vials and multiple sessions to create a successful result.

PLLA can be administered to the buttocks via cannula or needle, most commonly by a fanning or linear threading technique.42 The intended treatment plane is immediate subdermal to subcutaneous, with the treatment zone typically focused on the superior and lateral area of the buttocks.42 PLLA, like other injectable fillers, should be delivered under very clean to sterile conditions, with meticulous care to aseptic technique. Massage is recommended immediately after treatment and for several days following implantation. This may promote even product dispersion and reduce the risk of nodule formation.39 A common rule of thumb used in post-care instructions is the Rule of 5-5-5 – moderate circular massage for 5 minutes, 5 times a day, for the 5 days after treatment.

Outcomes

As PLLA’s effects rely on the body’s ability to simulate a controlled fibroblastic response, results following treatment typically take 3-6 months to manifest. PLLA is FDA-approved for 25 months in duration, with reports of at least 3 years duration.39,42 For addressing skin laxity of the buttocks, maintenance therapy is recommended every 18 months.43 It has been suggested that PLLA is a reasonable option for low BMI patients seeking gluteal are improvement that may not have reasonable adipose stores to provide meaningful results from autologous fat transfer (FIGURE 5).10,40,41

Very few studies have been conducted regarding PLLA for buttock enhancement despite the growing popularity of the product for body rejuvenation. Sadick and Mazzuco45 conducted a study of 15 female patients receiving PLLA treatment to the gluteal region. Subjects received 1 vial of Sculptra at a 10 mL total dilution combined with Nokor needle subcision to treat cellulite dimples. According to three blinded raters, at least 50% of patients had a two-grade global aesthetic improvement from baseline to after treatment.

Adverse Events/Precautions

The vast majority of adverse events following PLLA are mild, expected and temporary in nature. These include bruising, edema, and discomfort at the treatment site. Perhaps the most discussed and dreaded possible adverse event is papule or nodule formation, which occurs when PLLA is concentrated in a small are of placement. This can occur due to incorrect plane of injection, placement near dynamic areas of muscle movement, among other factors. With proper technique and injection into the subcutaneous compartment, the risk of nodule formation is exceedingly low, less than 1% for patients undergoing multiple treatment sessions on the face.46 Papules and nodules occur when PLLA product becomes concentrated, often due to error in injection depth technique or placement near areas of muscle hyperactivity. Non-facial papules and nodules may be less frequent due to the thickness of the subcutaneous compartment and a lack of superficial muscles in this anatomical region. Most PLLA papules are palpable but nonvisible and require only active observation. Nodules, if symptomatic, can be treated with appropriate therapy including subcision and mechanical disruption, oral tetracyclines, intralesional steroids or 5-fluorouracil, and very rarely, excision.39

Patients desiring large volume enhancement of the buttocks region with PLLA may find the prospect cost-prohibitive. Improvements in skin texture and quality often require fewer vials for an appreciable effect.

CaHA

Background

Radiesse (Merz North America, Raleigh, NC) is a biocompatible, resorbable, and biodegradable filler capable of collagen stimulatory effects.47 It is composed of calcium hydroxylapatite (CaHA) in a carobxymethylcellulose gel carrier and was FDA-approved in 2006 for subdermal implantation in the correction of moderate to severe facial wrinkles such as nasolabial folds. It is also FDA-approved for restoration of soft tissue loss associated with HIV lipoatrophy.48 In 2009, the FDA-approved the use of admixing lidocaine to 0.3% concentration to increase patient comfort during the injection procedure.

CaHA has a dual function as both an immediate volumizer and a collagen biostimulator. It is composed of a 30% concentration of 25-45 µm calcium hydroxylapatite spherical particles suspended in sodium carboxymethylcellulose gel.48 Over a period of 9-12 months, the gel is broken down by phagocytosis and the microspheres become encapsulated by collagen. The CaHA microspheres are gradually degraded through normal metabolic processing and eliminated through urine as calcium and phosphate ions, a process similar to bone mineral metabolism. 47

Treatment

Radiesse is supplied as a 1.5 mL syringe of product, and a second generation Radiesse+ comes with pre-incorporation of lidocaine without dramatic changes to the viscoelastic properties of the gel. Similar to other injectable fillers, treatment should be completed using aseptic technique with a needle or cannula. The intended plane of injection is the immediate subdermal to subcutaneous compartment.

Treatment is geared toward the intended result: volumization versus skin quality improvements. The admixing of local anesthesia or diluting agents is not just for patient comfort but also for the desired effect in a given patient. More concentrated product delivery with lower dilution volumes targets volume replacement and dermal remodeling. On the other hand, hyperdilute CaHA where dilution ratios reach greater than 1:1 with the admixing solution are better suited for targeting biostimulation.49 The concept in the latter hyperdilution technique is to delivery a thin and evenly distributed coating of the CaHA microspheres over a given surface area of treatment.49 A more dilute CaHA mixture (1:2 to 1:6 gel filler to mixing solution) will address skin laxity and texture, while a more concentrated form (1:1 or less) will accomplish structural or volume deficiencies.

Due to the ability to manipulate the concentration of CaHA microspheres to a treated region of the buttocks, varying dilution ratios can be tailored by the injector to target skin irregularities such as discrete cellulite dimples, striae dinstensae, skin aging and laxity, and mild volume deficiencies. 47 The superior and lateral quadrants of the buttocks should be targeted for improvements in skin laxity. More concentrated product can be used over the entire buttock region to address more discrete dimple-like cellulite (FIGURE 6).

Skin laxity hyperdilution ranges from 1:1 to 1:4 depending on the patient and area of treatment. 47 Dilution ratios are largely based off of skin thickness of the treated patient. Addressing cellulite dimples necessitates lower dilution volumes, typically in the range of 1:1 to 1:2. Because of the small volume syringes available in the U.S., large volume aliquots make larger scale volumization of the buttocks region with CaHA impractical.

A needle or cannula deliver can be used depending on patient factors and injector preference. If a needle is utilized, a short linear threading technique is effective in product delivery.

Consensus papers state about 1 syringe (1.5 mL) per buttocks is typically used per session to address skin irregularities, laxity, and quality. 47 Typically 2-3 sessions are completed for correction. Maintenance therapy is typically recommended every year to 18 months depending on individual patient response.

Outcomes

Neocollagenesis following CaHA implantation is well-studied. Dermal rejuvenation occurs through type I collagen & elastin production, as well as angiogenesis and fibroblast stimulation.48 The highest deposition of collagen I and elastin occur at four months post-injection and are maintained at nine months.49 A Decolleté study demonstrated an increase in both type I collagen and elastin formation. at 7 months post-injection.50 Another study by Silvers et al. observed an increase in skin thickness for 18 months after treatment in 91% of patients.51 Skin quality by both studies was found to be more elastic.

Adverse Events/Precautions

The majority of adverse events following CaHA are expected and mild in severity. Admixture of local anesthetic and CaHA reduces patient discomfort during the procedure. Swelling, bruising, and pain in the area of treatment are common following CaHA injection. 48

Injection plane and method as well as dilution volume may play an important role in mitigating possible adverse events following injection of CaHA. Similar to other injectable fillers, cannula use may afford less adverse events including bruising. 47 Inadvertent injection into muscle or vasculature can lead to a higher risk of product embolization of a vaso-occlusive event. Superficial placement of the product can lead to beading, visible white papules, or nodule formation.48 Injectable sodium thiosulfate (STS) was evaluated alone or in combination with topical application of sodium metabisulfite as a reversing agent for CaHA.52 This proof-of-concept study in a cadaveric porcine model found reduced CaHA microspheres upon histopathologic evaluation 24 hours after treatment. Further evaluation is necessary to determine the safety and effectiveness of STS as a reversing agent of CaHA.

PMMA

Background

Polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) has been applied to medicine for over 7 decades. It is used across multiple medical specialties from orthopedics to ophthalmology. PMMA is a constituent in bone cement and fixation screws, contact lenses, filler material in the correction of bony defects and vertebral stabilization for osteoporosis and fractures.53

Injectable PMMA (Artefill, Bellafill, Suneva Medical Inc., San Diego, CA) gained its first FDA-approval in 2006 for the correction of nasolabial folds. 48 It also has a 5-year indication for acne scarring. In Brazil, it is approved for the treatment of gluteal lipoatrophy in HIV patients.54

Injectable PMMA is a dual component device consisting of a gel suspension of 20% nonresorbable PMMA and 80% bovine collagen. 48 The carrier gel consists of 3.5% partially denatured bovine collagen, 92.6% phosphate buffer, and 0.9% sodium chloride. Injectable PMMA is considered synthetic, but biocompatible and chemically inert. The PMMA microspheres are 30-50 µm and uniform in size, a size large enough to avoid marcorphage phagocytosis. There are 6 million PMMA particles per mL of injectable PMMA material. 48

Considered a permanent filler, injectable PMMA has a long duration due to its proposed mechanism of action. The gel carrier is degraded within a period of one to three months. The remaining PMMA microspheres are recognized by the body’s immune system. A host response ensues that creates PMMA microsphere encapsulation and promotes neocollagenesis though fibroblast activation. 48 The earliest formulation of commercially-available injectable PMMA (Artecoll) had a less uniform particle size that could provoke a granulomatous reaction.55

Treatment & Outcomes

Due to the animal origin of the gel carrier, skin testing is required prior to filler placement to avoid allergic reactions to the product. 48 The largest worldwide experience on PMMA for body use comes from Brazil, where injectable PMMA is marketed under the name Metacrill (Nutricell, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil). A consensus paper of the Brazilian Symposium PMMA Aesthetics Expert Consensus Group panel detailed over 87,000 cases of injectable PMMA use on face and body.55 Of these cases, only 15% were corporal/off-face.

For gluteal treatment, PMMA injection is recommended in a deeper plane, either intramuscular or submuscular. Indications for buttocks treatment was typically tissue flaccidity and/or cellulite. Recommended PMMA injection volumes are 100-150 mL for the gluteal region during each treatment session.55 A 10 year cohort study examined 1681 patients treated with PMMA to the gluteal region from 2009-2018.53 The patient population had a mean age of 39 and less than 10% of patients were male. Over 54,000 mL of PMMA product was injected over 2770 gluteal filling sessions. On average, 237 mL of PMMA was injected during the first session, with 147 mL during the second, and 86 mL for the last session. Final injection volumes are dependent on the needs and capacity of each patient.55 The consensus paper deemed the procedure safe with effective results.

A second Brazilian paper published in 2015 detailed PMMA treatment to HIV-related gluteal lipoatrophy.56 In the study, 154 patients were injected with PMMA to the gluteal region. Patients were over 90% male with a mean age of 48.9 years old. Study subjects were administered NSAIDS and antibiotics post-procedure, and an average of 60 cc of PMMA was used per session with a total treatment range of 120 to 440 cc. The mean number of treatments sessions was three. Ninety-three percent of patients were satisfied with treatment.

Adverse Events/Precautions

According to the published Brazilian experience, less than 1% of implanted PMMA cases experience complications following treatment.55 A published retrospective study of Brazilian HIV gluteal lipoatrophy patients found a similar rate of low adverse events. With a follow-up period of six to 78 months, moderate pain and bruising were the most common and expected adverse events following PMMA injection. No infection or granulomas were observed. (Serra)

In the 10-year Brazilian consensus paper of PMMA facial and corporal treatment, adverse events occurred at the following rates in 1681 patients: infection (0.07%), hematomas (0.36%), seromas (0.29%), and ecchymoses (0.26%). According to the paper, 98.12% of procedures had no side effects.55

More significant adverse events following PMMA injection include late edema, implant site infection, seroma, necrosis from inadvertent intra-arterial injection, and chronic inflammatory reactions. To avoid vascular events, some have recommended and advocated for microcannula implementation for product delivery.55

Papules, over-correction fullness, and granulomas are the greatest concern for long-term adverse events.48 Granulomatous foreign body reactions to the PMMA molecule can occur iatrogenically or as a result of surgical trauma or systemic infection.55 Extreme cases of PMMA-induced granulomas have resulted in calcitriol-mediated hypercalcemia.57 The U.S. manufacturer’s data suggests a 1:1000 risk of granulomatous infection, and Brazilian data places the incidence at 0.296 to 0.332%. Treatment of granulomas may include intralesional steroids and 5-fluorouracil.48

Liquid Injectable Silicone Injections

Background

Medical-grade liquid injectable silicone (LIS) refers to silicone with standardization in terms of purity and viscosity. Medical grade LIS has a high viscosity of 360 centistokes and is extremely hydrophobic with low surface tension and volatility. It is inert, noncarcinogenic, translucent, and bacteriostatic.

Aesthetic use of medical-grade LIS is considered off-label.58 It is FDA-approved for ophthalmologic application for use in retinal detachment. However, LIS has been used for decades in aesthetic applications under the auspices of the FDA Modernization Act of 1997. This legislation allows provisions for any legally marketed FDA-approved device to be administered for any condition or disease within a doctor-patient relationship.48 This Act defines how physicians administer medications and devices in an off-label manner. A lack of well-conducted, prospective clinical trials along with the permanent, and occasionally unpredictable nature of LIS has made its use controversial.59

Adulterated, non-medical grade liquid silicone injected by non-licensed practitioners comprise many of the published reports on LIS complications in the medical literature.57,60,61 Large volume LIS implantation to the buttocks region is not recommended. Awareness of the illegal practice of non-medical grade silicone injections is important. Practitioners may encounter patients with this injection history and be called upon to manage potential long-term complications.

Treatment

LIS has been used in aesthetic medicine to augment soft tissues and utilized worldwide since the 1960s.58 Recommendations for injection of medical-grade liquid silicone conform to the microinjection technique. Orentreich first described the injection technique in 1995.62 After sterile preparation of the skin, LIS is administered to the area of volume loss using 0.01-0.03 mL droplets spaced at one to 10 mm intervals. Separations of microdroplets is theorized to lessen the opportunity of an inflammatory response, which is increased when larger quantities of LIS are used.58

A series of treatments occurring at 4-6 week intervals leads to collagen encapsulation of the LIS and gradual volume replacement. Overcorrection is not recommended, and larger aliquots of LIS droplets may compromise a smooth result.59,60

Outcomes

There have been no published clinical trials regarding usage of LIS in the buttocks region.

Adverse Events/Precautions

Rare, but devastating long-term adverse effects of LIS including physical disfigurement and the off-label manner of administration have prevented widespread use of medical-grade LIS.63 Adverse events following injection of liquid silicone can occur two to 25 years following injection.64 Mild complications include bruising, erythema, edema, and palpable small nodules known as beading.58 More ominous adverse events are disconcerting to both patient and physician and are summarized below.

Severe complications can occur with both medical-grade and adulterated LIS. Significant AEs with medical-grade LIS include ulcerations, recurrent cellulitis, and granulomatous responses.60,64 Adulterated silicone performed in nonprofessional conditions may lead to painful swellings, hyperpigmentation, infection, fibrosis, granulomatous reactions, vascular occlusion, DVTs/hypercoagulable sequelae, hypercalcemia, and retroperitoneal fibrosis.61

Granulomatous responses comprise many of the long-term adverse events associated with LIS. The mechanism of action is unclear, but a generalized foreign body reaction is suspected. T-cell activation follows, promoting cytokine production and TNF-alpha release that promotes granuloma formation. Silicone may also have the potential for biofilm formation with a protective polysaccharide coating on the bacterial source that is resistant to appropriate antibiotic treatment.60

Small granulomatous reactions can be treated first with massage and intralesional triamcinolone acetonide. Unsuccessful response to first-line treatment may necessitate topical imiquimod, and oral minocycline. Failure of second-line therapy of small granulomas may necessitate treatment with laser, liposuction, excision, or combination therapy.54

Diffuse or large granulomas require a more aggressive treatment approach. Similar to small granulomas, massage, intralesional triamcinolone and oral antibiotics may be used. Tetracycline, specifically oral minocycline or doxycycline are most often used to treat granulomas due to their anti-inflammatory effect.60 In cases of treatment failure, second -and third-line treatment of large and diffuse granulomas include a heterogenous group of treatments aimed at minimizing the granulomatous response or removing the LIS. This includes oral isotretinoin, etanercept, colchicine, allopurinol, tacrolimus, liposuction, MRI-guided excision with fat grafting, or any combination of the above.54,59-61 A review of 14 cases also found use of etanercept, oral clindamycin, NSAIDS, and topical 5% imiquimod used to treat cases of injection silicone granulomas with varying success.59,60

In extreme cases, rare and life-threatening hypercalcemia may result from LIS injection to the buttocks.58,65 Foreign-body inflammation of the granulomas cause calcification. Macrophages within granulomas are able to convert more active vitamin D, leading to increased calcium absorption from the digestive tract. Extra-renal CYP27B1 (aka 1-alpha-hydroxylase) is produced in abundance by activated macrophages in granulomas. This is believed to cause pathologic calcitriol production and resultant parathyroid-independent hypercalcemia.57 Management of metabolic derangements from calcified granulomas is difficult and includes IV hydration, bisphosphonates, systemic steroids, oral ketoconazole, and surgical excision of the granulomas. Unsuccessfully treated hypercalcemia and elevated vitamin D may lead to renal failure and even death.57

Bioalkylimide

Background

Bio-Alcamid (Polymekon Biotech Industry, Milan, Italy) is a permanent filler composed of 96% apyrogenic water and 4% polyalkylimide. It is a non-resorbable, biocompatible polymeric gel used to treat soft tissue deficits and is not FDA-approved for use in the U.S.

Treatment

Bioalkylimide is injected as a permanent filler under sterile or near-sterile conditions given the product’s longevity. It creates a fibroblastic response by the body resulting in a 0.02 mm thick collagen membrane surrounding the product. This encapsulation response to a permanent product is considered a liquid injectable endoprosthesis.66 Although use of bioalkylimide is most commonly applied to facial injections, corporal injection areas including the buttocks have been performed.

Outcomes, Adverse Events/Precautions

Although the product offers immediate and permanent correction of soft tissue deficits, it is not without considerable risk. Complications can occur years after injection, even without precedent trauma. Adverse events most commonly include capsule formation (FIGURE 7), dislocation and migration of the injectable, and infection.

There has been a dramatic rise in reports detailing complications long after bioalkylimide placement.67 One case report of off-facial treatment detailed complications following polyalkylimide placement to the buttocks to improve HIV lipoatrophy. The patient experienced an infection with E. coli that consisted of hard and painful soft tissue changes in the area of filler placement. Subsequent treatment required incision and drainage as well as a prolonged course of IV and oral antibiotics.

Microfocused Ultrasound

Background

Microfocused Ultrasound (MFUS, Ultherapy; Ulthera, Inc., Mesa, AZ) debuted in 2009 with FDA clearance for a noninvasive brow lift. In 2012, indication for treating and lifting lax tissue of the submentum and neck followed. MFUS is FDA-cleared for tissue lifting on the face, neck, and decollete, as well as for visualization of tissue targeting during the procedure, which is termed microfocused ultrasound with visualization (MFU-V). MFU-V does not yet have on-label indications in the buttocks region.

The proposed mechanism of action of MFU-V relies on targeted tissue heating and resultant new collagen formation, leading to a tightening and lifting response in the treated region. Thermal coagulation points, typically around 25 per “line” fired by the device, is emitted from the transducer head. These focused regions of heat are targeted towards connective tissue bands visualized during the procedure. Over the ensuing months following treatment, tissue remodeling and neocollagenesis occurs, resulting in tissue laxity improvements, skin tightening, and tissue lifting.68

The MFU-V platform consists of the central device housing, which includes an ultrasound screen and power source, as well as the treatment wand. Three different focal depths of treatment, 4.5, 3.0, and 1.5 mm, are possible by interchangeable transducers on the treatment head. Ultrasound energy from the transducers fires at 4 or 7 MHz, depending on the depth of transducer selected.

Treatment

MFU-V is conducted in the clinic setting and requires no downtime following treatment. Treatment typically involves at least two passes with two different depths, targeting connective tissue bands in the dermal, subdermal, and SMAS tissues in the area of focused treatment. Each pulse from the transducer head produces a line of 25 thermal coagulation points – focused ultrasound energy that heats tissue, creating tissue coagulation and collagen denaturation.69

Results are not immediate but require time to manifest thermal-stimulated neocollagenesis, usually on the order of 3-6 months. Comfort during the procedure is maintained through a variety of maneuvers, from topical to regional/local anesthesia, oral and intramuscular anxiolytics, NSAIDs, or even narcotic pain medication. Distraction tools such as vibratory devices may also play an important role in patient ease during treatment. A typical MFU-V takes approximately 45 to 90 minutes depending on the area of treatment to be covered. Patients may resume daily activities following treatment.

Outcomes

MFUS is FDA-cleared as a single treatment with a duration of 12 months, although clinical experience suggests results may persist longer, closer to 18 months to 24 months. The majority of published literature focuses on MFU-V applications to the face, neck, and decollete. However, several small, investigator-initiated studies have reported on MFU-V use in the buttocks region.

Goldberg conducted an open-label pilot study of 31 subjects with skin laxity to the buttocks region.70 The average age and BMI of subjects were 46.7 years old and 25.31 kg/m2, respectively. Unilateral treatment with the 4.5 mm and 3.0 mm transducers to the right buttock was administered using 25, 1-inch by 1-inch square grid across the inferiolateral gluteal region. An average of 973 lines were administered during the treatment session.

Results from this pilot study were mixed and modest. Only half of the masked assessments of baseline and day 180 digital images were correctly identified as before or after treatment due to the subtlety of effect. Physician- and subject-rated Global Aesthetic Improvement Scales (GAIS) were 81.5% and 74.1%, respectively, for overall improvement at day 180. Overall subject satisfaction was only 59.3%.

Possible limitations from the Goldberg buttocks laxity study included poor patient selection. Ten percent of their subject population was morbidly obese. It was postulated that better patient selection that included patients with correctly identified tissue laxity rather than tissue volume issues would have produced more meaningful results. This approach is echoed by a multimodal consensus paper; skin laxity as a primary focus of buttocks rejuvenation are likely to yield better results from MFU-V to improve skin quality, texture, tightening and lifting.71

Also in 2017, Casabona conducted a retrospective study evaluating the use of of MFU-V with calcium hydroxylapatite for cellulite in the buttocks region.72 Twenty female subjects with moderate to severe cellulite and a mean age 40, were treated with diluted CaHA and MFU-V to the buttocks and thigh region. In contrast to Goldberg’s study, this study included patients with low BMIs (average BMI of 21.5) and were targeted for cellulite treatment rather than overall skin laxity in the buttocks region.

In the retrospective MFU-V and diluted CaHA study, subjects received treatment with MFUS at a depth of 4.5 mm at 4MHz, followed by the 7 Mhz, 3 mm depth transducer. Immediately following ultrasound treatment, patients received a 1:1 dilution of CaHA with local anesthetic administered through a fanning cannula technique. Two blinded evaluators found a statistically significant improvement in cellulite severity. Skin biopsies from volunteer subjects demonstrated histologic evidence of type I and III collagen, with conversion to type I peaking at month three following treatment.

Adverse Events/Precautions

Generally speaking, MFU-V is well-tolerated. Expected adverse events following treatment are typically mild in nature and rarely interfere with return to work or daily activities. These include mild soreness, edema, or possible bruise in the treatment area, which resolves within a period of days to a few weeks. In Casabona’s retrospective study,72 all treatments were considered well-tolerated and no significant adverse events were noted.

The most common discussed adverse events following MFU-V is pain during administration, and a lack of efficacy. In the Goldberg study,70 study subjects found treatment relatively uncomfortable. Subjects received topical numbing one hour prior to treatment but 28 of 31 patients elected to have reduced energy settings due to discomfort associated with MFU-V. Mean pain scores ranged from 6.6 to 6.9 depending on the depth of transducer used. Only three subjects elected to have the left buttock treated at the conclusion of the study.

Lack of effectiveness following treatment may be due to a myriad of factors. Poor patient selection, unrealistic patient expectations, and improper or ineffective treatment parameters all may play a role in the perceived and actual effectiveness of MFU-V. Patients with mild skin laxity and a desire for a nonsurgical option for skin tightening are often ideal candidates. Proper training, and constant visualization of tissues during treatment allows for proper ultrasound energy delivery to intended tissue targets (connective tissue and SMAS) rather than ineffective energy delivery to muscle, bone, or fat.68

HIFEM

Background

All previous nonsurgical and surgical methods of aesthetic buttock enhancement have relied on treatment of the skin and/or fat layers. High Intensity Electromagnetic (HIFEM) technology was FDA-cleared in 2018 as the first non-surgical, noninvasive method of body contouring through muscle targeting 73 Magnetic stimulation has previously been used for enhanced resistance training, improvement of the cough reflex, and strengthening of pelvic floor muscles.74

HIFEM technology uses very low frequency (3-5kHz) magnetic waves delivered at intensity up to 2.5 Tesla through 1 or multiple treatment paddles to create supramaximal muscular contraction of the treatment area.75 Initial FDA-clearance for HIFEM technology was for muscle targeting of the abdomen and buttocks. The clearance label has now expanded to treatment of the arms, thighs, and calves.

The HIFEM device utilizes alternating electrical current to create oscillating magnetic waves. These waves are created by a coil within the treatment applicator. The magnetic energy passes through tissues without effect. However, the magnetic energy causes depolarization of motor neurons affecting somatic muscle, thus causing involuntary, full muscle contraction. A pulse pattern has been developed to maximize muscle training and recovery. In October 2020, a second-generation HIFEM device was debuted with an improved pulse pattern that allows for 20% more active contraction during a treatment cycle. This device also contains a simultaneous and synchronized radiofrequency element within the applicator, allowing dual treatment of fat and muscle in desirous areas, such as the abdomen.76

Treatment

HIFEM therapy is applied with two treatment paddles to the buttocks region, one per side. The applicator is applied directly over the skin and desired muscle group to recruit muscular contraction during active treatment. In the case of the buttocks, the gluteal muscle group is targeted (FIGURE 8).

A treatment series consists of 4 weekly treatments. Each treatment session lasts 30 minutes. During a treatment session, using the original HIFEM device, a total of 20,000 contractions are elicited in the treatment area. No downtime is required following treatment, and patients may resume regular daily routines immediately following treatment.

Outcomes

HIFEM technology is well studied on the abdomen and buttocks. Published computed tomography (CT), ultrasound, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies have been completed on the abdomen demonstrating muscle thickening of 14-15.4% with the first generation HIFEM device. A porcine abdominal model demonstrated muscle hypertrophy and increase in muscle mass density of 20.56%.73

Specific to the buttock region, Jacob et al completed a multicenter, prospective study to evaluate the safety and effectiveness of HIFEM treatment to the buttocks region for lifting and toning.77 Seventy-five subjects received a total of four, 30-minute treatment sessions, and they were followed through one month post-treatment. Patient satisfaction was evaluated. In subjects that were initially dissatisfied with their buttocks region, they reported an 85% improvement in the appearance of their buttocks, which was statistically significant. According to investigators, physical improvement in the buttocks was more pronounced in patients with lower BMI scores who led an active lifestyle.

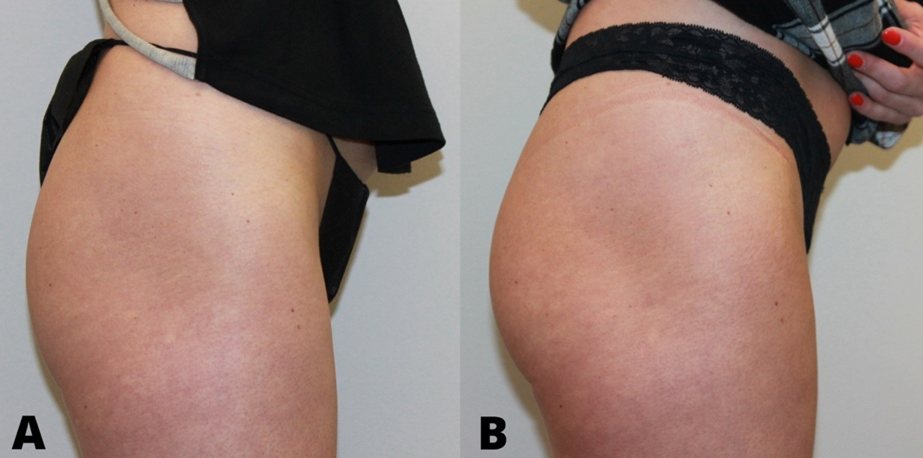

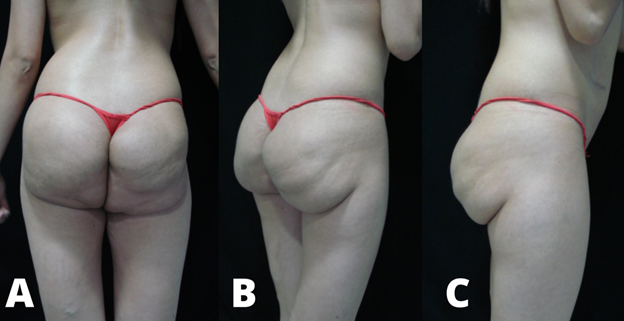

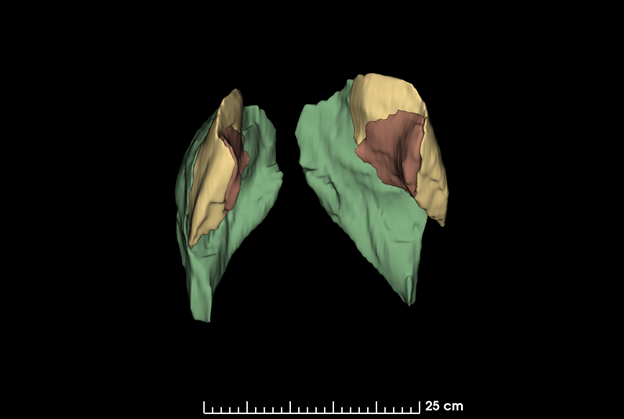

An MRI study of the buttocks demonstrated muscle hypertrophy of all three gluteal muscle groups following 4 treatment sessions.78 This prospective, single-center study evaluated 7 patients at baseline, 1 month, and 3 months following 4 HIFEM treatments to the buttocks. Three-dimensional volumetric analysis of MRI findings calculated muscle mass gain in the gluteus maximus, medius, and minimus. At 3-month follow-up, muscle mass increased by 13%, with the most pronounced hypertrophy in the superior pole of the buttocks region. Visible buttock lifting was visible on photographic evaluation (FIGURE 9).

Published results from HIFEM treatment show sustained muscle hypertrophy at 6 month follow-up without re-treatment.79 Maintenance therapy is recommended, however, typically at 3 or 6 month intervals.

Adverse Events/Precautions

Unlike electrical muscle stimulation (EMS) or transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS), there is no pain or risk of burns to the skin with HIFEM. Over 500,000 treatments have been administered with the original HIFEM device with no significant adverse events. All published clinical studies show an absence of significant adverse events. Expected and mild adverse events following treatment are infrequent but include muscle soreness, swelling, bruising, cramping, or erythema of the overlying skin in the treatment area.73

Summary

Rejuvenation of the gluteal region has sustained increased popularity and research in recent decades. A systematic framework of gluteal evaluation and identifying patient desires helps to achieve successful outcomes. Surgical approaches to gluteal enhancement are successful but not without risk. Nonsurgical options of buttock augmentation have expanded offering minimal downtime, low risk alternatives to gluteal implants and liposuction and autologous fat transfer. Nonsurgical options can address genetic, physiologic, and aging changes associated with the skin, fat, and muscle. Careful consideration of each nonsurgical option includes its advantages, risks, possible adverse events, and long-term outcomes. Nonsurgical buttock augmentation methods can be combined together and sometimes with surgical options. Gluteal rejuvenation is likely to continue to gain popularity, and become more sophisticated in its approach with future research efforts and refinement of technology and technique.

REFERENCES

- Bartels RJ, O’Malley JE, Douglas WM, et al. An unusual use of the cronin breast prosthesis. Plast Reconstr Surg 1969;44(5):500.

- Aiache AE. Gluteal recontouring with combination treatments: Implants, liposuction, and fat transfer. Clin Plastic Surg 2006;33:395-403.

- Mendieta CG, Sood A. Classificaiton system for gluteal evaluation revisited. Clin Plastic Surg 2018;45:159-177.

- “The international study on aesthetic/cosmetic procedures performed in 2016” at International Society of Aesthetic and Plastic Surgery. Available at: https://www.isaps.org/wpcontent/uploads/2017/10/GlobalStatistics.PressRelease2016-1.pdf. (Accessed August 21, 2020)

- Tijerina JD, Morrison SD, Nolan IT, Parham MJ, Richardson MT, Nazerali R. Celebrity Influence Affecting Public Interest in Plastic Surgery Procedures: Google Trends Analysis. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2019;43(6):1669-1680. doi:10.1007/s00266-019-01466-7

- Tijerina JD, Morrison SD, Nolan IT, Vail DG, Lee GK, Nazerali R. Analysis and Interpretation of Google Trends Data on Public Interest in Cosmetic Body Procedures. Aesthet Surg J. 2020;40(1):NP34-NP43. doi:10.1093/asj/sjz051

- Mofid MM, Teitelbaum S, Suissa D, et al. Report on mortality from gluteal fat grafting: Recommendations from the ASERF task force. Aesthet Surg J. 2017;37:796–806.

- Frank K, Casabona G, Gotkin RH, et al. Influence of Age, Sex, and Body Mass Index on the Thickness of the Gluteal Subcutaneous Fat: Implications for Safe Buttock Augmentation Procedures. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019;144(1):83-92. doi:10.1097/PRS.0000000000005707

- Halaas Y, Duncan D, Bernardy J et al. Activation of skeletal muscle satellite cells by a device simultaneously applying HIFEM and novel synchrode RF technology: Fluorescent microscopy facilitated detection of NCAM/CD56. Oral abstract presentation at the Annual Meeting of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery, 2020 Phoenix, AZ.

- Lin MJ, Dubin DP, Khorasani H. Poly-L-Lactic Acid for Minimally Invasive Gluteal Augmentation. Dermatol Surg. 2020;46(3):386-394. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000001967

- Ali A. Contouring of the gluteal region in women: enhancement and augmentation. Ann Plast Surg. 2011;67(3):209-214. doi:10.1097/SAP.0b013e318206595b

- Mendieta CG. Classification system for gluteal evaluation. Clin Plastic Surg 2006;33:333-346.

- Centeno RF, Sood A, Young VL. Clinical anatomy in aesthetic gluteal contouring. Clin Plastic Surg 2018;45:145-157.

- Ghavami A, Villanueva NL. Gluteal augmentation and contouring with autologous fat transfer: Part 1. Clin Plastic Surg 2018;45:249-259.

- Villanueva NL, Del Vecchio DA, Afrooz PN, Carboy JA, Rohrich RJ. Staying safe during gluteal fat transplantation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2018;141:79–86)

- Shah B. Complications in gluteal augmentation. Clin Plastic Surg 2018;33:179-186.

- Bruner TW, Roberts TL, Nguyen K. Complications of buttocks augmentation: Diagnosis, management, and prevention. Clin Plastic Surg 2006;33:449-466.

- De la Pena JA, Rubio OV, Cano JP et al. History of gluteal augmentation. Clin Plastic Surg 2006;33:307-319.

- Cardenas-Camarena L, Duran H. Improvement of the gluteal contour: Modern concepts with systematized lipoinjection. Clin Plastic Surg 2018;45:237-247.

- Coleman KM, Pozner J. Combination Therapy for Rejuvenation of the Outer Thigh and Buttock: A Review and Our Experience. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42 Suppl 2:S124-S130. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000000752

- Centeno RF, Young VL. Clinical anatomy in aesthetic gluteal body contouring surgery. Clin Plastic Surg 2006;33:347-358.

- Centeno RF. Autologous gluteal augmentation with circumferential body lift in the massive weight loss and aesthetic patient. Clin Plastic Surg 2006;33:479-496.

- Gonzalez R. Buttocks lifting: How and when to use medial, lateral, lower, and upper lifting techniques. Clin Plastic Surg 2006;33:467-478.

- Mendieta CG. Intramuscular gluteal augmentation technique. Clin Plastic Surg 2006;33:423-434.

- Siparsky PN, Kirkendall DT, Garrett WE. Muscle changes in aging: understanding sarcopenia. Sports Health 2014;6:36–40.

- Melton LJ, Khosla S, Crowson CS, O’Connor MK et al. Epidemiology of sarcopenia. J Amer Geriatrics Soc 2000;48:625-630.

- Palm MD. MRI evaluation of changes in gluteal muscles following treatments with the High-Intensity Focused Electromagnetic (HIFEM) procedure. Dermatol Surg 2020 (in press).

- Evans WJ. Skeletal muscle loss: cachexia, sarcopenia, and inactivity. Am J Clin Nutr 2010;91:1123S–1127S.

- Volpi E, Nazemi R, Fujita S. Muscle tissue changes with aging. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 2004;7:405–10.

- Rosique RG, Rosique MJF. Augmentation Gluteoplasty: A Brazilian Perspective. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2018;142(4):910-919. doi:10.1097/PRS.0000000000004809

- Singh D, Dixson BJ, Jessop TS et al. Cross-cultural consensus for waist-hip ratio and women’s attractiveness. Evol Hum Behav 2010;31(3):176-81.

- Vartanian E, Gould DJ, Hammoudeh ZS, Azadgoli B, Stevens WG, Macias LH. The Ideal Thigh: A Crowdsourcing-Based Assessment of Ideal Thigh Aesthetic and Implications for Gluteal Fat Grafting. Aesthet Surg J. 2018;38(8):861-869. doi:10.1093/asj/sjx191

- Aboudib JH, Serra F, de Castro CC. Gluteal augmentation: technique, indications, and implant selection. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;130(4):933-935. doi:10.1097/PRS.0b013e31825dc3da

- Lee EI, Roberts TL, Bruner TW. Ethnic considerations in buttock aesthetics. Semin Plast Surg. 2009;23(3):232-243. doi:10.1055/s-0029-1224803

- De Meyere B, Mir-Mir S, Peñas J, Camenisch CC, Hedén P. Stabilized hyaluronic acid gel for volume restoration and contouring of the buttocks: 24-month efficacy and safety. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2014;38(2):404-412. doi:10.1007/s00266-013-0251-9

- Claude O, Romain B, Pigneur F, Lantieri L. Treatment of HIV-infected subjects with buttock lipoatrophy using stabilized hyaluronic acid. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open 2015;3:e466.

- Camenisch CC, Tengvar M, Hedén P. Macrolane for volume restoration and contouring of the buttocks: magnetic resonance imaging study on localization and degradation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;132(4):522e-529e. doi:10.1097/PRS.0b013e31829fe47e

- Valantin MA, Aubron-Olivier C, Ghosn J, Laglenne E, Pauchard M, Schoen H, Bousquet R, Katz P, Costagliola D, Katlama C. Polylactic acid implants (New-Fill) to correct facial lipoatrophy in HIV-infected patients: results of the open-label study VEGA. AIDS. 2003 Nov 21;17(17):2471-7. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200311210-00009. PMID: 14600518.

- Palm M, Chayavichitsilp P. The “skinny”on Sculptra: a practical primer to volumization with poly-L-lactic acid. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012 Sep;11(9):1046-52. PMID: 23135646.

- Jabbar A, Arruda S, Sadick N. Off Face Usage of Poly-L-Lactic Acid for Body Rejuvenation. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017;16(5):489-494.

- Lorenc ZP. Techniques for the optimization of facial and nonfacial volumization with injectable poly-l-lactic acid. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2012;36(5):1222-1229. doi:10.1007/s00266-012-9920-3

- Haddad A, Menezes A, Guarnieri C, et al. Recommendations on the Use of Injectable Poly-L-Lactic Acid for Skin Laxity in Off-Face Areas. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019;18(9):929-935.

- Palm M, Goldberg DJ, Lorenc P, Ejehorn M et al. Immediate use after reconstitution of a a biostimulatory poly-L-lactic acid injectable implant. Oral abstract presentation at the Annual Meeting of the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery October 2019, Chicago, IL.

- Lin MJ, Dubin DP, Goldberg DJ, Khorasani H. Practices in the Usage and Reconstitution of Poly-L-Lactic Acid. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019;18(9):880-886.

- Mazzuco R, Sadick NS. The use of poly-l-lactic acid in the glutal area. Dermatol Surg 2016;42(3):441-443.

- Palm MD, Mayoral F, Rajani A, Goldman M et al. Chart review presenting safety of injectable PLLA used with alternative reconstitution volume for facial treatments. J Drugs Dermatol 2020 (in press).