The authors declare no conflicts of interest with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article.

The authors received no financial support for the research and/or authorship of this article.

Introduction

The aging face comprises many commonly observed characteristics including facial elongation, prominent nasolabial folds, brow ptosis, peri-orbital hollowing, atrophy of the midfacial fat pads, skin laxity, temporal wasting and jowling. These changes typically progress in a predictable fashion, and are predominantly driven by three distinct processes: 1) loss of soft tissue elasticity, 2) gravity-mediated descent of normal structures, and 3) loss of volume. More recent studies suggest that loss of volume, or deflation, may be the primary process driving these age-related changes.1 Cadaver studies by Rohrich et al. delineate the facial fat compartments,2 which become more discrete as age related volume loss occurs. Volume loss may occur early in the aging process,15 and volume restoration with soft tissue fillers can adequately address volume loss without the need for invasive surgical procedures during the early stages of aging.3,4

Injectable soft tissue fillers are widely used to address areas of facial volume loss and wrinkles. Many soft tissue filler materials are available on the market, including hyaluronic acid, calcium hydroxylapatite, poly-l-lactic acid, polymethyl methacrylate, and silicone.3 Perhaps the most popular, hyaluronic acid (HA) is a naturally occurring compound that composes the extracellular matrix of human connective tissue. The HA compound is a glycosaminoglycan disaccharide composed of alternately repeating units of D-glucuronic acid and N-acetyl-D-glucosamine.3,5 The resulting long unbranched chain is hydrophilic, enabling it to hold up to 1000 times its weight in water and leading to increased volume and turgor.3 Until 2007, it was thought that hyaluronic acid-based fillers worked exclusively by adding directly to dermal or subdermal volume. However, more recent studies based on observations that fillers create long-lasting results past what would be expected based on the biological availability of filler suggest that HA fillers may also directly stimulate collagenesis and fibroblast activity.6

Dermal fillers have been used for facial rejuvenation for over 20 years. Restylane® was the first HA filler to be approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2003, and was initially marketed to address deep wrinkles and folds and later for lip enhancement.7,8 Since that time, a wide array of products have come onto the market, with various characteristics and marketed for different indications. These products are differentiated by physicochemical properties that can predict how they will behave in vivo. The goal of this chapter is to outline the rheologic properties and manufacturing characteristics of HA fillers in order to help the practitioner understand which products are best suited for specific indications.

Manufacturing Process

Because hyaluronic acid is a naturally-occurring component of the human skin, HA-derived fillers are well-suited for use in facial rejuvenation, are associated with a low risk of allergic reaction and do not require skin testing prior to injection.9 Their effects are reversible and may be broken down by injection of exogenous hyaluronidase, if needed. Today’s commercially-available HA fillers are all manufactured through a similar process, which involves isolating hyaluronic acid in its original form by fermentation of Streptococcus sp. bacteria and then linearizing individual HA chains. Because the aqueous form of HA would be degraded rapidly in vivo, the HA chains must next undergo a stabilization process to prevent rapid in vivo enzymatic and oxidative degradation. The stabilization process involves joining individual molecules of HA together using cross-linking molecules. Butanediol diglycidyl ether (BDDE) is the crosslinker in most United States Federal Drug Administration (FDA) approved HA filler products, including the Restylane® and Juvederm® families of products, as well as Belotero Balance®.9,10 Because chemical cross-linkers can be irritating and can incite a foreign body reaction in the skin, any residual active stabilizer must be removed from the product after the cross-linking process. While gels characterized by a higher degree of cross-linking may tend to be longer-lasting, they are also less easily reversed with hyaluronidase and can affect the biocompatibility of the filler, resulting in rejection, encapsulation, or delayed onset inflammatory events.9

After the cross-linking step, each manufacturer uses a proprietary technology to modify their products, unique to each line of filler. This generates either particulate or nonparticulate HA fillers. Since the crosslinked HA product exists in block form after crosslinking, the proprietary modification is necessary to create gels that flow through small gauge needles with acceptable extrusion forces.5 During the manufacturing process of nonanimal stabilized hyaluronic acid (NASHA) fillers, which include the Restylane® family of products, blocks of gel are pushed through screens of various sizes to create much smaller particles with the final products composed of particles in a range of sizes. From a clinical standpoint, particle size influences clinically relevant properties such as dermal integration and longevity, as well as the extrusion force through a needle.9

In contrast, non-particulate gels including Belotero Balance® (cohesive polydensified matrix technology), are not sieved in this manner.8 Instead, they can undergo a second round of cross-linking to create a homogenous network of long HA chains within the gel mass.9 This homogeneity gives a smooth gel consistency, though these gels are dependent on degree of crosslinking, rather than particle size, to produce greater filling power and longevity. Belotero Balance® is also unique in that it is characterized by nonuniform cross linking, so that some areas are softer due to less dense crosslinking, while other areas are firmer because of denser crosslinking.8 Of note, the Juvéderm Vycross products Voluma®, Volbella®, and Vollure® are the only available HA fillers that consist of crosslinked long and short HA chains, while other products contain only long HA chains. The clinical relevance of these properties will be discussed later in this chapter.

Rheology

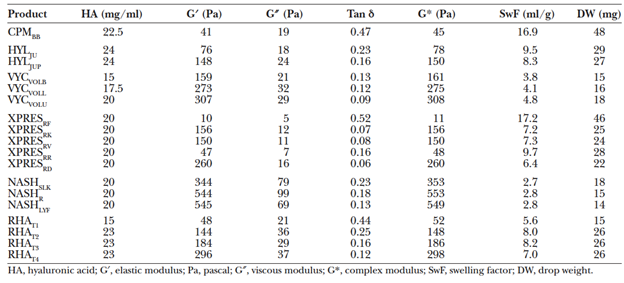

The manufacturing process for various commercially-available HA fillers has direct implications for the unique gel properties and clinical applications of these products. These gel properties can be described using the science of rheology, which describes the consistency and flow properties of a liquid or gel.9 Relevant rheologic parameters include HA concentration, degree of cross-linking, gel firmness, cohesivity, and swelling factor, among others.

Hyaluronic acid concentration

HA concentration is defined as the total weight of HA in 1 milliliter (mL) of product, typically expressed in milligrams (mg) per mL. The molecular weight of HA is proportional to the number of repeating disaccharides, in the form of cross-linked and non-cross-linked molecules.11 Thus, the total HA concentration represents the sum of insoluble (cross-linked) HA gel and soluble, or free, HA. However, only cross-linked HA resists in vivo degradation and contributes to the gel’s effectiveness, so it is important to note what percentage of a filler’s HA concentration is cross-linked.5

Cross-linking

As noted above, cross-linking of HA molecules in commercially-available fillers in the U.S. is typically achieved by adding BDDE modifications to purified HA molecules. The BDDE modifications can react at both ends to link two separate strands of HA, resulting in a crosslink. However, the BDDE may bond only at one end to a HA strand, leaving the other end free. When BDDE modification does not result in a HA crosslink, this is termed a pendant crosslinker. Pendant modifications have a minimal impact on gel firmness, but do influence the degree of gel swelling and can also lead to an increased risk of foreign body reaction by increasing the degree of modification (MoD) of the gel.5

Total % degree of modification = % cross link + % pendant

Although cross-linking improves the longevity and volumizing ability of the product in vivo, a MoD that is too high can cause problems with biocompatibility. The body may cease to recognize as hyaluronic acid, leading to a foreign body or a delayed onset immune reaction.12 The highly modified gel is also less easily degraded or broken down by the injection of hyaluronidase.

The clinically relevant properties of a filler product are highly influenced by the degree of crosslinking. As gels become more highly cross-linked, the distance between the cross-linked segments is reduced. This in turn causes an increase in the firmness and strength of the gels, requiring greater forces to cause gel deformation. Degree of crosslinking however, is not the only factor that influences gel firmness. Other factors that contribute to a gel’s clinical behavior will be discussed below.

Elastic Modulus (G’)

Gel firmness is most commonly interpreted as a function of the elastic or storage modulus (G’), which is a measure of a product’s ability to resist deformation.5 It can also be conceptualized as the amount of energy that a gel can store.8

A gel with a higher G’ is considered a “firmer gel” and is ideal when there is a need for deep, targeted product deposition with less distribution of product into the surrounding tissues. However, because high G’ products resist deformation, they may feel firmer within the tissues.9 The G’ is dependent on several factors, including the cross-linking density, the HA concentration, and the presence of unbound HA.12

Gel Viscosity

Gel viscosity is quantified by the viscous modulus, or G double prime (G″). G” can be considered as a gel’s resistance to dynamic forces and is also known as the loss modulus. A higher G’’ gel is thicker and requires a greater extrusion force to be expressed through a needle (e.g. peanut butter, rather than syrup).

G” is a measure of a gel’s ability to dissipate energy when force is applied, and this sense is reciprocally related to G′ (the ability to store energy).

Together, G’’ and G’ define the complex modulus, or G*, which represents a gel’s total resistance to deformation, and is determined by the following formula:13

G* = (square root of (G’)2 + (G’’)2)

While fillers are viscoelastic, the elastic component is much more significant and the G’ value is much larger than that of G”. As such, G* and G’ are almost identical. G’ is more widely reported and considered a proxy for G*.5,12

Tan delta is a measure of a gel’s balance of elasticity versus viscosity, and is defined by the ratio of G” to G’.

Tan delta = G’’/G’

Gels characterized by a high tan delta, with values close to 1, are predominantly viscous (e.g. honey), while those characterized by a low tan delta, with values near 0, are predominantly elastic (e.g. gelatin).11

Swelling factor

The swelling factor describes a gel’s ability to take up fluid in-vitro while maintaining a single phase.11,12,14 In contrast to aqueous solutions, gels uptake water to a finite degree before phase separation occurs. The addition of more water than a gel can uptake causes separation into a slurry of gel particles within a solution. In this way, the swelling factor indicates a gel’s water saturation status. When nearly saturated with water, and close to equilibrium, a gel will swell less after injection when compared with unsaturated gels below equilibrium.

The swelling factor is inversely proportional to the term cmin, which is equivalent to the HA concentration of a fully swollen gel without any unbound HA molecule. Therefore, a low cmin reflects a higher swelling factor, and vice versa.

Swelling factor = 1/cmin

In general, the swelling factor is inversely related to G’, 5,12 as highly crosslinked gels with a higher HA concentration are limited in their ability to incorporate water molecules given that HA molecules are closely associated with one another.11

Cohesivity

A more newly recognized rheologic parameter, cohesivity, represents a gel’s capacity to remain intact and not dissociate when subject to vertical compression, or stretching forces. It can be conceptualized as the force between particles that holds them together within a gel. Cohesivity is dependent on the product’s HA concentration and the crosslinking technology, as these determine the structural network of the gel. It is thought that higher cohesivity predicts better intradermal integration, as the material is less likely to disperse into surrounding tissue.5

To date, cohesivity has earned limited scientific recognition as an appropriate property for product comparison because of the lack of a standardized measurement technique.5 Various cohesivity assays exist,14 and recent studies have attempted to validate and compare a standardized reference scale to interpret these assays, with the Cavard-Sundaram Cohesivity Scale being one such example.15

It has been observed that gels with a high G’ generally demonstrate lower cohesivity, whereas low G’ or low HA concentration does not necessarily predict high cohesivity.14 Moreover, there is a strong positive correlation between swelling factor and cohesion, such that a greater degree of cross-linking often translates to a lower cohesion and a lower swelling factor.11,14 These observations have prompted some experts to question whether a measure of cohesion is necessary, as other physicochemical parameters such as G’ and swelling factor may be sufficient to describe various gel properties.14

Flexibility

Traditional rheologic parameters, including G’, are determined under nearly static conditions. Recent studies aim to define a new rheologic parameter, flexibility, which describes how fillers perform in a dynamic environment. This can be measured in the setting of an amplitude sweep, where the amount of deformation, or strain, applied to a gel is gradually increased. Flexibility is important to consider in order to determine how fillers will behave under moving or stretching conditions (i.e. dynamic facial movements).

During an amplitude sweep, when a gel is deformed to the extent that it can no longer return to its original shape, and behaves more as a liquid than a solid, it has reached its yield point. Ohrlund likens this phenomenon to a bottle of tomato ketchup, which moves little until shaken sufficiently and then starts to flow.16 A gel that can withstand a greater deformation before reaching its yield point is considered to have greater flexibility. The flexibility can be quantified by a term referred to as xStrain:14

xStrain = strain value at the G’’/G’ cross-over point during an amplitude sweep

Injection Considerations

To safely obtain natural-looking results with dermal fillers, an understanding of facial anatomy and appreciation for the patterns of change in the aging face are essential. Prior to injection, the prudent clinician considers the aesthetic goal of the procedure, anesthesia, the product, depth and anatomic location of injection with special attention to possible complications, volume of product to be injected, the instrument to be used for injection (cannula versus needle), as well as the gauge of the instrument. No one product is optimal to achieve every single aesthetic goal, and the rheologic properties described above must be considered when choosing the specific product and the injection tool. Specific product families will be discussed in the Clinical Applications section of this chapter.

Aside from product choice, depth of injection in each anatomic area must be carefully considered given the risk of complications that include skin necrosis, vascular injury, filler embolization, and blindness. A thorough discussion of filler related complications is however, beyond the scope of this chapter.

With regard to anesthesia, some dermal filler products contain lidocaine, assisting with patient comfort while filling. There is literature to suggest that the addition of lidocaine changes the rheologic properties of the fillers,17 though the extent of change may differ from product to product. Additional anesthetic, if used, is typically applied topically in a cream or gel form. Commonly used topical anesthetics prior to dermal filler injection include compounded benzocaine-lidocaine-tetracaine, lidocaine-prilocaine, or one of these components alone.

Hyaluronidase is an endogenous enzyme that degrades hyaluronic acid in vivo and is a useful tool to reverse injected hyaluronic acid filler. Specifically, hyaluronidase can be used to eliminate inflammatory nodules or bumps resulting from HA filler injection, treating overcorrection with HA filler, or in the setting of complications from HA filler injection including intra-arterial injection.18 When undesirable nodules occur in the post-procedure period, the dose of hyaluronidase administered typically ranges from 3 to 75 units, and is usually administered in conjunction with an antibiotic. In the case of vascular injury, up to 75 units of hyaluronidase may be administered and ideally applied within 4 hours. Late application of hyaluronidase (> 24 hours) has not been shown to be effective in preventing skin necrosis.

Clinical Applications of Rheology

Nonanimal stabilized hyaluronic acid (NASHA) fillers include the Restylane® family. The products in this family of filler are available in a variety of particle sizes, from Restylane® Silk, a small particle HA product at 200,000 gel particles/mL, to Restylane®-L, composed of medium density particles at 100,000 particles/mL to large particle Restylane® Lyft (formerly Perlane-L®), which contains 8,000 gel particles/mL.19 The G’ and viscosity of the NASHA products is high, and increased with particle size in Fagien’s study (2019). Sundaram et al. (2015) found the cohesivity of Restylane® and Restylane® Lyft to be low compared to the Hylacross, Vycross, and Cohesive Polydensified Matrix families of products.

In general, tissue distribution after intradermal injection can be predicted by product G’, viscosity and cohesivity.15, 20-22 Restylane® and Restylane® Lyft, with high G’ and viscosity but low cohesivity, can be expected to take the form of small boluses in the dermis. These properties lend these products to subcutaneous or supraperiosteal placement, to provide firm structure and lift23 in cases of age-related midface volume. In patients with adequately thick skin and subcutaneous tissue, these products could be considered for injection into the deep dermis/superficial subcutis for severe facial/nasolabial folds. However, in thin skinned patients or in areas with thin skin, product visibility on facial animation can be a concern given the tendency for vertical lift and limited tissue integration afforded by high G’ and viscosity. Swelling factor is low for the NASHA products, and limited water uptake is expected after injection.11

The Hylacross products include Juvéderm Ultra® and Juvéderm Ultra Plus®, while Juvéderm Voluma®, Volbella®, and Vollure®, are made with Vycross technology. Juvéderm Ultra Plus®, and Ultra®, with intermediate cohesivity, viscosity and G′ provide a balance of vertical tissue lift and horizontal tissue expansion. These products are well suited for injection into the mid to deep dermis23. Juvéderm Ultra Plus® and Ultra® are FDA approved for correction of moderate-to-severe facial wrinkles and folds (e.g. nasolabial folds), but are also commonly used for lip augmentation. A moderate swelling factor11 suggests that the Hylacross products will draw in more water than the NASHA products after injection. In contrast, the Vycross products have a swelling factor higher than that of the NASHA products but lower than that of the Hylacross products,11 and intermediate fluid uptake should be expected.

Belotero Balance® is a Cohesive Polydensified Matrix product with low G’ and viscosity, but high cohesivity. It is homogeneously distributed within the dermis after injection15 and can be considered for more superficial placement given its tendency for uniform integration, as likelihood of product bolus visibility is lower. When injected intradermally, Belotero Balance® lends itself to tissue expansion with horizontal spread, rather than vertical lift.8 Given its moderate swelling factor,11 a larger amount of fluid uptake can be expected after injection. It is indicated for injection into the mid-to-deep dermis for correction of moderate-to-severe facial wrinkles and folds, such as nasolabial folds, but use in the tear troughs and lateral canthal lines has been described.11 Of note, Belotero Balance® has been reported to cause less of the Tyndall effect,8 which results in a bluish discoloration at the site of superficial filler injection. Hyaluronic acid boluses in the superficial dermis can scatter light, causing blue light, which has a shorter wavelength, to be preferentially reflected back to the observer, to cause the bluish hue. Because of its dermal distribution, Belotero Balance® boluses are more unlikely after injection, and this prevents the preferential blue light scattering that can cause discoloration with superficial injection of other products.8

In summary, the rheologic properties of a HA filler product are determined by a combination of the HA chain lengths, HA concentration, degree of HA crosslinking, the crosslinker material, and proprietary post-crosslinking modifications. In turn, these rheologic properties, when considered with individual patient anatomy and specific aesthetic goals, should inform the clinician’s choice of dermal filler product. As the number of FDA approved dermal filler products continues to increase, an understanding of each product’s rheologic properties may influence a clinician’s decision to consider the product for indications other than those explicitly published.

References

- Lambros V. Models of facial aging and implications for treatment. Clin Plast Surg. 2008;35(3):319-317. doi:10.1016/j.cps.2008.02.012

- Rohrich RJ, Pessa JE. The fat compartments of the face: anatomy and clinical implications for cosmetic surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;119(7):2219-2231. doi:10.1097/01.prs.0000265403.66886.54

- Greco TM, Antunes MB, Yellin SA. Injectable fillers for volume replacement in the aging face. Facial Plast Surg. 2012;28(1):8-20. doi:10.1055/s-0032-1305786

- Sundaram H, Cassuto D. Biophysical characteristics of hyaluronic acid soft-tissue fillers and their relevance to aesthetic applications [published correction appears in Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013 Nov;132(5):1378]. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;132(4 Suppl 2):5S-21S. doi:10.1097/PRS.0b013e31829d1d40

- Kablik J, Monheit GD, Yu L, Chang G, Gershkovich J. Comparative physical properties of hyaluronic acid dermal fillers. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35 Suppl 1:302-312. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2008.01046.x

- Landau M, Fagien S. Science of Hyaluronic Acid Beyond Filling: Fibroblasts and Their Response to the Extracellular Matrix. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;136(5 Suppl):188S-195S. doi:10.1097/PRS.0000000000001823

- Restylane FDA approval letter. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/pdf4/p040024a.pdf

- Sundaram H, Cassuto D. Biophysical characteristics of hyaluronic acid soft-tissue fillers and their relevance to aesthetic applications [published correction appears in Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013 Nov;132(5):1378]. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;132(4 Suppl 2):5S-21S. doi:10.1097/PRS.0b013e31829d1d40

- Beasley KL, Weiss MA, Weiss RA. Hyaluronic acid fillers: a comprehensive review. Facial Plast Surg. 2009;25(2):86-94. doi:10.1055/s-0029-1220647

- Stocks D, Sundaram H, Michaels J, Durrani MJ, Wortzman MS, Nelson DB. Rheological evaluation of the physical properties of hyaluronic acid dermal fillers. J Drugs Dermatol. 2011;10(9):974-980.

- Fagien S, Bertucci V, von Grote E, Mashburn JH. Rheologic and Physicochemical Properties Used to Differentiate Injectable Hyaluronic Acid Filler Products. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019;143(4):707e-720e. doi:10.1097/PRS.0000000000005429

- Edsman K, Nord LI, Ohrlund A, Lärkner H, Kenne AH. Gel properties of hyaluronic acid dermal fillers. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38(7 Pt 2):1170-1179. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2012.02472.x

- Pierre S, Liew S, Bernardin A. Basics of dermal filler rheology. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41 Suppl 1:S120-S126. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000000334

- Edsman KLM, Öhrlund Å. Cohesion of Hyaluronic Acid Fillers: Correlation Between Cohesion and Other Physicochemical Properties. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44(4):557-562. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000001370

- Sundaram H, Rohrich RJ, Liew S, et al. Cohesivity of Hyaluronic Acid Fillers: Development and Clinical Implications of a Novel Assay, Pilot Validation with a Five-Point Grading Scale, and Evaluation of Six U.S. Food and Drug Administration-Approved Fillers. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;136(4):678-686. doi:10.1097/PRS.0000000000001638

- Öhrlund, Å. Evaluation of Rheometry Amplitude Sweep Cross-Over Point as an Index of Flexibility for HA Fillers. Journal of Cosmetics, Dermatological Sciences and Applications. 2018;8:47-54. doi: 10.4236/jcdsa.2018.82008.

- Micheels P, Eng MO. Rheological Properties of Several Hyaluronic Acid-Based Gels: A Comparative Study. J Drugs Dermatol. 2018;17(9):948-954.

- Cavallini M, Gazzola R, Metalla M, Vaienti L. The role of hyaluronidase in the treatment of complications from hyaluronic acid dermal fillers. Aesthet Surg J. 2013;33(8):1167-1174. doi:10.1177/1090820X13511970

- Bertucci V, Lynde CB. Current Concepts in the Use of Small-Particle Hyaluronic Acid. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;136(5 Suppl):132S-138S. doi:10.1097/PRS.0000000000001834

- Flynn TC, Sarazin D, Bezzola A, Terrani C, Micheels P. Comparative histology of intradermal implantation of mono and biphasic hyaluronic acid fillers. Dermatol Surg. 2011;37(5):637-643. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2010.01852.x

- Micheels P, Besse S, Flynn TC, Sarazin D, Elbaz Y. Superficial dermal injection of hyaluronic acid soft tissue fillers: comparative ultrasound study. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38(7 Pt 2):1162-1169. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2012.02471.x

- Micheels P, Sundaram H, Besse S, et al. Ultrasonographic and histological comparison of 3 hyaluronic acid gels. Paper presented at: 2014 International Master Course on Aging Skin Annual Congress; January 30–February 2, 2014; Paris, France.

- Bass LS. Injectable Filler Techniques for Facial Rejuvenation, Volumization, and Augmentation. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2015;23(4):479-488. doi:10.1016/j.fsc.2015.07.004